Julius Eastman’s “Stay On It” Incessantly

February 26, 2022

New York, N.Y.

American music has a tradition of quirky individualism. I’m thinking Charles Ives, John Cage, Morton Feldman, Conlon Nancarrow, George Crumb, Terry Riley. Which of these composers is not like the others? All of them!

To this group must also be included Julius Eastman:

Born in 1940 in New York City, Eastman studied at Ithaca College and then the Curtis Institute of Music, graduating in 1963 with a degree in composition. He had a successful musical career in the sixties and seventies, but it later derailed, and in the 1980s, he became homeless and periodically drug-dependent. He died in obscurity in a Buffalo hospital at the age of 49.

In recent years, Julius Eastman has been undergoing a revival as performance editions of his music have been published, and his compositions performed by major orchestras and chamber ensembles. Musically, he is is roughly categorized as a proto-minimalist who combined repetitive structures with improvisation and aleatoric elements, sometimes giving them provocative titles attesting to his Black and gay militancy.

I’ve been celebrating Black History Month on Facebook with daily postings of YouTube videos of music by Black composers throughout the centuries. (I will soon be consolidating those entries into a single blog post.) Day 16 was Julius Eastman, and I posted a video of his oddly spelled 1974 composition Femenine.

But in the process of exploring YouTube for performances of Julius Eastman’s music, I noticed many videos of his 1973 composition Stay On It. I wondered: Exactly how many are there?

Stay On It is instantly recognizable by its initial incessant syncopated riff. (Technically, it’s a Cuban son clave 3-2 rhythm.) Yet, within the composition, there is much room for flexibility. Every performance is different, and it can explode into raucous chaos, or slide back into subdued contempation. It can sound like free jazz; it can sound like Steve Reichian minimalism or even approach the quiet flowing ripples of Morton Feldman or John Luther Adams. But in whatever direction the music goes, it usually remains quite joyful.

In the 2016 article “Minimalist Composer Julius Eastman, Dead for 26 Years, Crashes the Canon”, New York Times music critic Zachary Woolfe writes:

At the core of “Stay on It” (1973) is a bright, relentless riff over which a vocalist merrily sings the title. But improvised, wheezing, almost trippy passages emerge; the tight rhythmic order dissolves. When the opening riff returns, it’s slower and warmer, proceeding through chromatic transformations that are sometimes queasily dissonant, sometimes hopeful. By the end, there’s just a single piano playing, and, finally, the constant vibrating pulse of a tambourine.

Stay On It was somewhat less admired when it was first performed. Prior to that 2016 article, the previous time that the composition was mentioned in the New York Times was December 7, 1973, when Donal Henahan reviewed a concert at Carnegie Recital Hall of new music that he dismissed as “a glorification of monotony":

Monotony in a loud variety came in Julius Eastman’s “Stay On It” (1973). While Mr. Eastman, at the piano, chanted his own metapoetry in a piercing falsetto, six other instruments, amplified, hammered out an eight‐note motive that occasionally shifted perspective because of overlaid patterns and phase‐shifts.

In the 2017 article “Julius Eastman’s Guerrilla Minimalism”, New Yorker music critic Alex Ross writes:

In 1973, Eastman wrote “Stay on It,” which begins with a syncopated, relentlessly repeated riff and a falsetto cry of “Stay on it, stay on it.” There’s a hint of disco in the festive, propulsive sound. But more dissonant, unruly material intrudes, and several times the piece dissolves into beatless anarchy. (A good rendition can be found on the New World set; even better is a dynamic 1974 performance from Glasgow, available on Vimeo.) “Femenine” extends the mood of “Stay on It” to more than an hour’s duration, losing wit and variety in the process.

By the “New World set,” Ross is referring to the three-CD set Julius Eastman: Unjust Malaise released in 2005 and largely reponsible for introducing Eastman’s music to the general public. The album is on Spotify, but if you’ve recently cancelled your subscription, you can also find the same track on YouTube. This is a recording of a life performance at SUNY Buffalo on December 16, 1973. It is one of the few performances during Julius Eastman’s lifetime that the work was performed without him at the piano:

The following video of the 1974 Glasgow performance of Stay On It is in terrible shape but it’s a valuable historical artifact. Julius Eastman introduces the piece, plays the piano, and does vocals; percussionists are Jan Williams and Dennis Kahle; Amram Chodos is on clarinet; and Benjamin Hudson is on violin:

These two performances are certainly similar but with many differences. They have become vitally important because the original score of Stay On It has been lost, and it’s not quite certain what that score was like. Today, people use scores that have been created based largely on these recordings. A score published by Schirmer is available, and a few pages can be examined on that website. Although the instrumentation is flexible, almost always a piano and percussion are involved. Notice also a poem by Eastman that serves as a preface. Sometimes this poem is read in performance; sometimes not. This document also has a score that has been reversed engineered from the Buffalo performance.

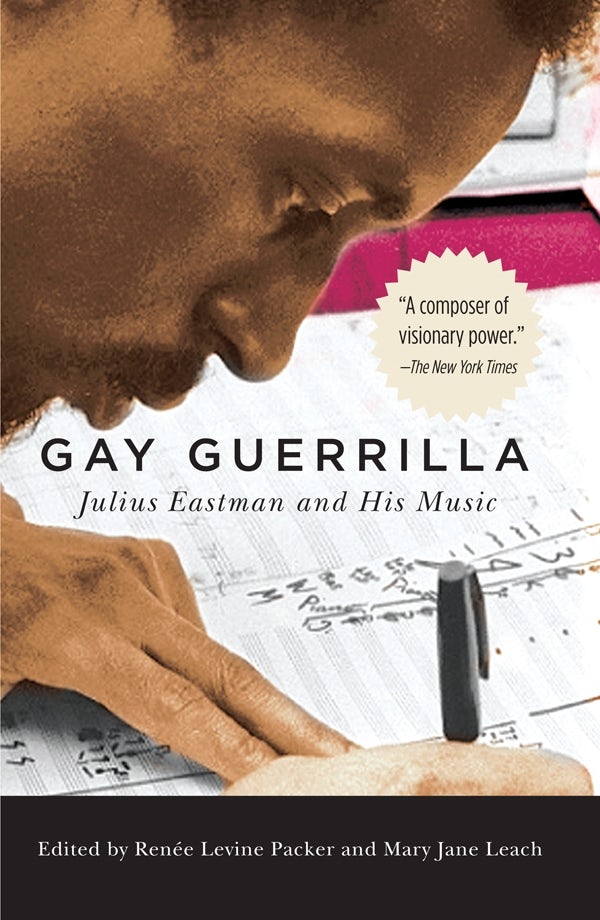

In an essay on Stay On It in the book Gay Guerrilla: Julius Eastman and His Music (University of Rochester Press, 2018), Matthew Mendez ultimately finds the work elusive, and the essay is disturbingly titled with a quotation by cellist David Gibson: “That Piece Does Not Exist Without Julius.” Mendez asks: “would Eastman even have wanted the work revived after he was gone?”

But even to speak of Stay On It as a “work” is misleading. If it is a musical work, where does that work reside? In some vanished “conductor’s score” ... ? In one of Stay On It’s recordings? All of them, somehow “averaged” together? ... Perhaps Stay On It is better understood in terms of nonreproducible performance art, with each iteration being part of the same “series,” yet ineluctably distinct... To resuscitate Stay On It may be to violate the spirit of the music, but it is undoubtedly the most persuasive testament to Eastman’s overflowing creativity. The alternative, alas, is silence. (pp. 168–9)

Under the assumption that silence is not the preferred alternative, Stay On It has been performed many times in recent years, often combining the fragmentary scores with attempts to channel Eastman’s musical spirit.

How many performances of Stay On It would you guess are available on YouTube and Vimeo? Four? Eight? Twelve? Oh ye of little faith! I found so many that I didn’t know at first how I could possibly order them, so I did it by the length of the video, from shortest to longest, from 6 minutes 45 seconds to 30 minutes 30 seconds.

The earliest of these performances date from 2015; others were posted fairly recently. Many of them are by student or semi-professional ensembles, others by well-known groups. It’s quite fascinating to see what people do with this composition, demonstrating its malleability without ever losing touch with its essential identity.

The shortest online performance is a 2020 collaboration among several independent arts organizations, remotely performed by musicians and dancers, and posted by Lincoln Center. It is dedicated to frontline workers during the pandemic.

The UNA Contemporary Ensemble is affiliated with the University of North Alabama. This 2021 performance breaks several times into Stay On It’s characteristic chaotic section:

The Eugene Difficult Music Ensemble “performs and commissions underrepresented experimental works in order to open ears and minds.” Yeah, that applies. This video was posted in 2021:

The wind noise picked up by the microphones adds a nice aleatoric element to this 2021 backyard performance posted by Arizonian violinist Gabrielle Dietrich:

Here’s CELLOHIO, the Ohio Statue University Cello Ensemble, performing in 2017 in Columbus Ohio. They sometimes add their voices to the instruments, and apply some bow-on-cello-body action for a percussive effect.

This video definitely has the largest ensemble of all these performances, and a conductor is needed. The description indicates that it is “Performed by a mixed instrumental pickup-group of teachers at the 2019 Weill Institute Summer Music Educators Workshop at Carnegie Hall’s Weill Hall.” It’s not Weill Recital Hall, but another space in the complex.

Here’s a 2017 performance by socially undistanced musicians associated with the Timucua Arts Foundation, an arts and education institution based in Central Florida:

The following is one of two performances featuring bassoonist Joe Qiu who made his own transcription of Julius Eastman’s music based on the Glasgow performance. These musicians seem to be based in London. The video was posted in 2017:

This is a vibrant performance by musicians at the 2016 Switchboard Music Festival in San Francisco:

This pandemic virtual ensemble includes 29 students from Obelin Conservatory, mostly from the graduating class of 2020 but some from the classes of 2021 and 2023. They begin by reading the poem that prefaces the published score:

This is the same performance, but preceded by a 43-minute discussion about the process and experience of putting it all together.

This is an Atlanta-based contemporary music ensemble called Bent Frequency performing in 2019 at Georgia State University. It is a generally relaxed performance with moments of quiet beauty:

Bassoonist Joe Qiu posted this video of a percussion-centric 2018 performance in Peckham, a district in South London. Notice the audience members sitting over at the right:

This performance posted in 2016 is by the arts organization Tetractys New Music, based in Austin. At times, the drummer gives this performance more of a rock vibe, and the long slow quiet ending is nicely done.

The Concept Store Quartet is an unusual assemblage of violinist, saxophonist, percussionist, and accordionist based in Basel. This 2020 performance certainly has second quirkiest instrumentation (after the six cellos):

The Late Music Ensemble featured in the next video from 2016 is based in York in England. They regularly perform at the York Unitarian Chapel on the first Saturday of March through October, I suspect because Anglicans wouldn’t allow such a thing in their churches:

The 208 Ensemble is based in 208 area code Boise, Idaho (but you knew that). This 2019 performance unfortunately has no video, but it goes in some interesting directions, including a sung interlude by actress, performer, educator, activist, radio host, and Boise State alumna Leta Harris Neustaedter:

This 2021 performance by students at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music includes electric guitars, a keytar, and lots of dancing. If I were a young musician, this is where I would want to go to college!

The following performance was recorded in 2015 at Church of the Advent Library in Boston based on a transcription prepared by the keyboardist Paul Pinto:

Members of the New Music Ensemble at the Cleveland Institute of Music enter one by one to join the festivities in this 2016 performance. As the music is fading out towards the end (plot spoiler!) they all exit.

The Sō Percussion quartet is one of the country’s outstanding new-music ensembles. Here they have collaborated with MEDIAQUEER to perform Stay On It for a recording available in 2021 on streaming platforms. Little windows sometimes show glimpses of the actual performance:

This is another 2021 video posted by Sō Percussion, and the description reads “Performed by students of the Sō Percussion Collaborative Workshop.” That’s all I know, but much vocalizing is involved:

This YouTube video is the same, but the description contains a more detailed list of the personnel.

Here’s a 2021 performance from Cologne, Germany, performed by 11 women (including dancers) of the Julius Eastman Project at Week-End Fest X. The audience is standing for the duration of the half-hour performance.

Finally, the longest video of Stay On It is by prominant American new music ensemble Alarm Will Sound. They have invited some friends here to bring the musician count up to about 20. This performance took place at Sheldon Concert Hall in St. Louis Missouri in 2018:

Perhaps someday I will even see a live performance!