Building a Virginal: Feeling Like I’m Just Getting Started…

May 17, 2023

Roscoe, N.Y.

Today I finished installing all the jacks in my Zuckermann Troubadour Virginal with Celcon plectra and red cloth dampers:

This work (and some other tasks I’ll describe here) occurred on May 12, 13, 16, and 17, which I’m calling Virginal Construction Days 24 through 27.

It may seem from the photo like I’m basically finished, so why do I feel like I’m just getting started?

Because these keys may look fine but most of them don’t work very well. Some are too loud; some are too soft. Some require lots of force to press; others are quite light. Most of the jacks drop back into place after plucking the string, but many others “hang” and can’t be triggered again until I manually push them down, and that’s not good when both my hands should be on the keyboard.

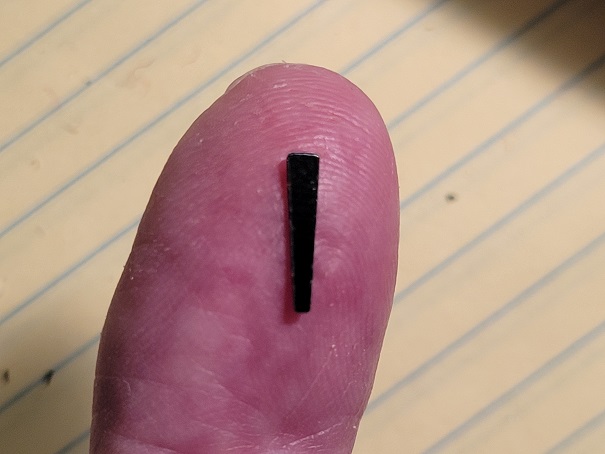

The big difference between a hand-crafted keyboard instrument and one that’s been mass-produced (or electronic) is that each key is unique. Over this series of blog entries, I’ve chronicled assembling the individual keys of the keyboard, and stringing the wires across the soundboard, but the real difference in the keys results from the only pieces of plastic used in the virginal, the Celcon plectra:

This plectrum goes in a little slot in each jack to pluck the string.

Yes, they’re tiny, but they’re still too thick and clunky to properly pluck the string, so they must be carved up a bit with an X-Acto knife. (The process is called “voicing”) The sound that a plucked string makes — and the force required to pluck it — depends on several factors: how far the string is from the jack (which despite much care is somewhat inconsistent), and the size and shape of the plectrum, the carving of which is an acquired skill that I have not yet acquired.

In my previous blog entry, I installed 20 jacks with plectra and dampers so that I could play the first four measures of Bach’s C-Major Prelude from Book 1 from the Well-Tempered Clavier. But It was messy and uneven because the keys required different amounts of force to press. Fortunately this Prelude doesn’t include any chords because playing chords was terrible.

Someone who read my blog kindly directed me to a web post on piano “touchweight,” which is word I didn’t know but seemed like I should. Searching that word with “harpsichord” directed me to a page in the Harpsichord section of the Piano Technicians Guild website. The response by Fred Sturm included a ballpark (“75-125 grams”) and links to three talks he gave on the harpsichord with notes and pictures that relate to this and other issues.

One of Fred Sturm’s photos shows a weight sitting on a key, and I tried that, but I didn’t really like it because I wanted to measure what the existing touchweight was for each key. I had to juggle multiple weights for that (moving the 50-gram off, moving the 20-gram on, and so forth) and they wouldn’t stay put. So I built a little gizmo to hook on the side of the virginal and hold the weights:

But I didn’t like this either. Moving the weights on and off was too messy. I finally figured out that what I needed is sometimes called a Force Gauge or a Force Meter or a Push-Pull Meter because you can also use it to measure weight. The one I got cost about $50 and it has Peak and First Peak modes. The First Peak mode was ideal for measuring the force required to press the key because the first peak occurs when the string is triggered:

The readings are a little erratic, so I did a few of them for each key and kind of averaged the two more central readings in my head and sometimes rounded them. Here’s what I jotted down for the 20 keys I had installed:

| Key | Touchweight in Grams |

|---|---|

| B♭ 3 | 100 |

| B 3 | 221 |

| C 4 (middle C) | 94 |

| C♯ 4 | 195 |

| D 4 | 141 |

| E♭ 4 | 213 |

| E 4 | 96 |

| F 4 | 203 |

| F♯ 4 | 180 |

| G 4 | 210 |

| G♯ 4 | 183 |

| A 4 | 175 |

| B♭ 4 | 183 |

| B 4 | 190 |

| C 5 | 165 |

| C♯ 5 | 240 |

| D 5 | 198 |

| E♭ 5 | 220 |

| E 5 | 160 |

| F 5 | 195 |

This is not good! The keys that are about 100 grams seem about right, although maybe I want them a little lighter. I’m not sure. (And yes, I am well aware that the gram is a measure of mass rather than force, but most of us are more comfortable with grams than newtons.)

Unfortunately, this is not like a computer program where you can just set a constant, and run through a loop, and everything is adjusted accordingly. Every change has to be made individually, and if a plectrum is carved too small, it must be replaced, and the carving process for that one starts over.

This is why I feel that all I’ve done so far has been merely prep work, and now the real job begins.

But not quite yet. Starting tomorrow, I’m going to be spending some time in New York City until May 28 or 29. Work on the virginal will then resume with my best attempts to give a fundamental consistency to every key’s sound and feel.