In Praise of Don Lancaster

July 1, 2023

Roscoe, N.Y.

In 1977, I had a Univox Electronic Piano that had stopped working well, and I had an idea that I could adapt the core electronics into an electronic music sequencer — a device that repetitively plays a sequence of notes. But I had no idea how to do this. My adolescent forays into electronics and four years at an engineering and science school had given me only a background in analog circuits. Consequently, I imagined some kind of electro-mechanical wiper switch.

Fortunately, the original Barnes & Noble store on 17th Street and 5th Avenue (before it was a chain) had a good electronics section where I found a book entitled CMOS Cookbook that had recently been published. This book was a revelation! Not only was I given an excellent tutorial in digital logic, the book also contained clear and concise descriptions of actual CMOS chips, providing the crucial link between theory and construction. CMOS Cookbook was the perfect book for me at exactly the right time.

That book was by Don Lancaster, who I am sorry to say died last month at the age of 83.

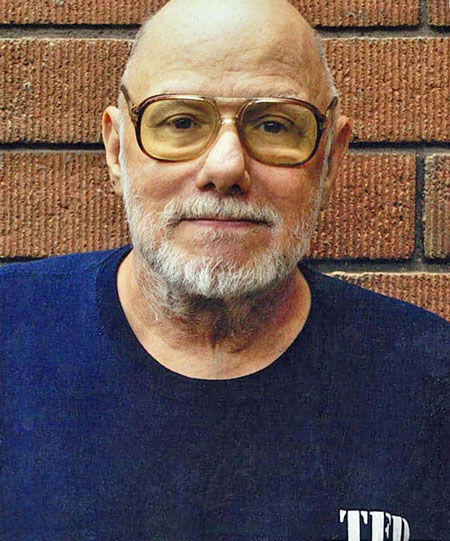

I leaned about Don Lancaster’s death from a Facebook post by my old friend Jeff Duntemann. Lancaster’s obituary (from which I took the above photo) appeared in the Gila Herald. I never met Don Lancaster, and I don’t think I’d ever seen a photograph of him.

I can’t emphasize enough how important Don Lancaster’s book was to my life and career. I think I spent more time with CMOS Cookbook than any other book before or since. My original copy eventually fell apart into many loose pages.

CMOS Bookbook was a springboard for several years of immersion into using digital logic chips to build electronic music instruments (as described in my online essay Adventures in Electronic Music: Beeps, Bloops, and Klangs: 1974–1983). I used CMOS chips to build an electronic music sequencer based on the guts from the Univox electronic piano, followed by a programmable sequencer based around a tone-generation chip described in Lancaster’s book. When I came across an article in the second issue of the Computer Music Journal on the design of a digital synthesizer, I knew how I could build such a thing, and I eventually did. I used Don Lancaster’s TTL Cookbook when I abandoned CMOS for working with the faster TTL chips, and his TV Typewriter Cookbook for building a circuit for a video display. With this background in digital logic, the transition to working with 8080 and Z80 microprocessors and assembly language came fairly smoothly.

When the insurance company where I worked got IBM PCs, I was able to learn 8086 assembly language and write some handy programs. Getting my own IBM PC in early 1984 led to my writing for PC Magazine and getting a beta copy of the Microsoft Windows SDK, which led to my first book.

Most importantly, however, at some point I realized that my background in digital logic was not common among the wider public and even among many of my colleagues in the computer industry. That led me to conceive and write my book about digital logic Code: The Hidden Language of Computer Hardware and Software, the first edition of which was published in 1999.

Without Don Lancaster’s CMOS Cookbook, I don’t think any of this would have happened.