Our Books, Our Selves

September 24, 2007

New York, N.Y.

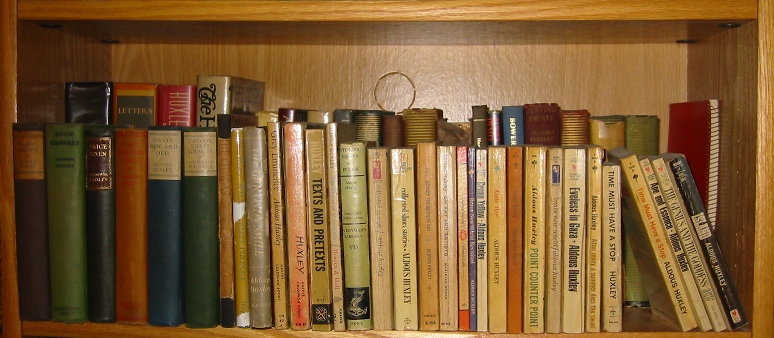

This is a bookshelf in my home that for obvious reasons I think of as the Aldous Huxley Shelf:

These are books by and about Aldous Huxley. Most of the books on this shelf were purchased by my teenage self between 1967 and 1971. To make maximum use of available bookshelf space, they are arranged in two rows with the larger books in the rear — a technique of shelving books pioneered by, I believe, James Boswell.

My Aldous Huxley Shelf may be a bit excessive, but I don't think it's unusual. Many of the literate people I know have similar enclaves of related books on their shelves, revealing a time in their lives when they burrowed down deep in a particular genre or author. Our books are a history of our lives. In the formation of my identity, these books are as important as my parents and my teachers.

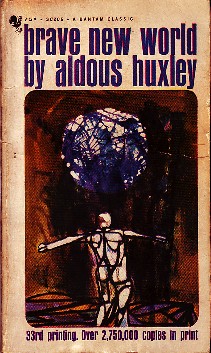

My infatuation with the works of Mr. Huxley began, of course, with Brave New World. The paperback edition I have has a print date of August 1967, which probably means I was 14 when I bought it and first read it:

I think I read it about six times over the next few years. Brave New World is one of the classic dystopias, of course, but I also understood it as a social satire, and a commentary on our times as well as a view of the possible future. I figured the man who had written this probably had written other worthwhile texts, so I began to seek out other novels Huxley had written.

I think what impressed me most about Huxley was that he seemed to know about everything. Science, literature, art, music, philosophy, religion, history — this was a level of learning and knowledge clearly beyond anything I could hope for from the public schools of New Jersey. I felt it was necessary to supplement my formal education with reading, and part of this plan involved reading more Huxley.

In 1968, when I was 15, my mother began letting me take the bus into New York City by myself. I quickly gravitated towards Book Row, the legendary array of used bookstores that once dotted 4th Avenue and Broadway between St. Mark's and 14th Street. By the late 60s, most of them were already gone, but I think there were still about a dozen still in business. (By the time I graduated college in 1975 and moved to the neighborhood, only The Strand was left.)

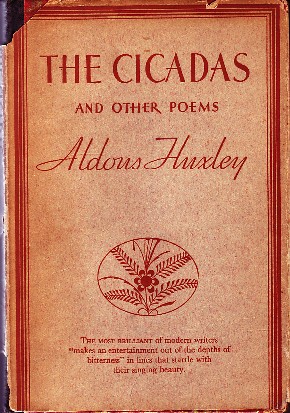

In these stores I would browse for hours, and particularly investigate what out-of-print Aldous Huxley books happened to be waiting for me on the shelves. This is how I got many of the more obscure Huxley volumes of essays, travelogues, histories, and even some poetry. This one, published in 1931, still had its dust jacket.

I'd pay a couple bucks for each book, take them home, and devour them within a day or two.

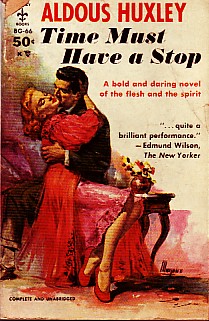

I remember that I had managed to find all of Huxley's eleven novels in paperback editions except for Time Must Have a Stop (1944). I was with my mother in some used bookstore we had gone into when I spotted this one on a revolving display case:

The juxtaposition of the lurid cover and tag line with the blub by Edmund Wilson still cracks me up. I later found a more "proper" paperback edition of Time Must Have a Stop that still has the original sales receipt stuck in its pages:

That, or course, is the original Barnes & Noble store located for decades on 5th Avenue and 18th Street long before the store became a chain.

Why do I even keep all these books? I'm obviously never going to read them again. A few of them might actually be worth a couple bucks on the used-book market.

I have no good answer to this question except that these books — all my books — seem as much a part of me as the hands that first touched them 40 years ago, and the eyes that first read them. I own nearly every book I've purchased and read in the past 40 years, including many I have not found time to read.

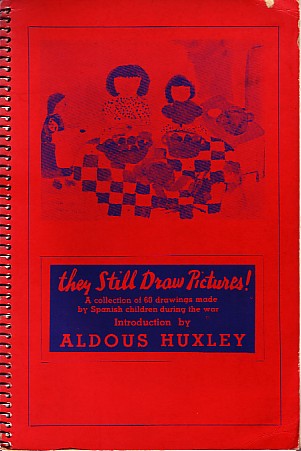

Even now I occasionally come across something to add to the Aldous Huxley Shelf. The most recent addition is from a few years ago: Whenever Deirdre and I drive up to Utica to visit Deirdre's mother and sister, we make a point of going to the Berry Hill Book Shop in nearby Deansburo. There, while pawing through the new arrivals, I pulled out a spiral-bound book I knew about but had never seen.

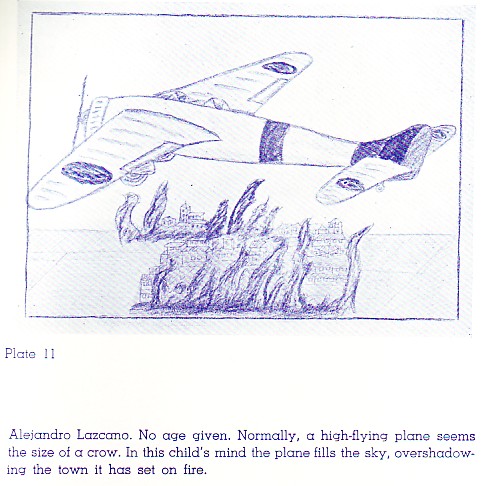

This book was published in 1938 by the Spanish Child Welfare Association of America, an organization connected with the American Friends Service Committee (Quakers), and contains 60 drawings (unfortunately not reproduced in color) made by children during the Spanish Civil War, each with a brief description:

The original price of They Still Draw Pictures! was $1. I paid $30 — a bargain for this excellent copy. I could probably "complete my collection" of Huxley books with a little time on ABE, and while I've used ABE extensively (mostly to obtain old books on computers and programming) it just wouldn't be the same as the serendipitous finds.

Books are perhaps the most fundamental man-made objects of our culture. Each book encapsulates a portion of someone's life and mind that they have laboriously assembled into a coherent narrative. Each book is often awarded a special layout and cover by its publisher that symbolizes its unique nature. Our bookshelves are chaotic displays of different colors, sizes, widths, and typefaces because each book is as unique as the person who created it and the world encapsulated within.

Going over to someone's apartment or house with a well-stocked bookcase is an adventure of discovery and recognition. It's always odd seeing the same editions of one's own books on other people's shelves. But a connection and resonance is established across space and time through the mutual books we've read.

Scientists and philosophers have long recognized the fallacy of the dualism of René Descartes — the idea that the contents of the mind are essentially different from (and not a product of) the physical brain and body. The concept of a mind that exists apart from the physical brain is an absurdity.

Yet, we can extract from each book a couple hundred thousand ASCII codes and leave the printed book behind as a carcass, and we'd be hard-pressed to quantify exactly what has been lost. Those couple hundred thousand ASCII codes can go into making a newer edition with a different cover and whiter acid-free paper, and you certainly won't find me complaining. Regardless how much fun it might be to read nothing but first editions from the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries, modern paperbacks are so much more convenient.

Increasingly, however, we are promised that those couple hundred thousand ASCII codes will not form the basis of a printed book but will remain disembodied to be downloaded into an iThing of some sort, where they will compete for space with YouTube videos and this week's pop hits.

I can't help thinking that this is the most degrading thing you can do to a book — to strip it of its corporeal foundation and treat it as yet another worthless byte stream, to substitute the look and feel of paper and ink with an ugly hunk of shining plastic. How much worse can we insult and cheapen books than by convincing ourselves that they don't deserve to be treated special — that they shall no longer have an exalted stature on the bookshelves in our homes?

I would feel much more comfortable with the demise of print if the people celebrating this transition actually seemed to care about books, and if they spoke of books as something more than repackaged and downloadable byte streams. One chronicler of this printless future recently said in his blog "like it or not, technology is here to stay," as if we are obliged to be slaves to all digital possibilities regardless how destructive they may be of the actual activity they are supposed to enhance.

The teenager of tomorrow will be blissfully ignorant of the dangerous interiors of used-book stores, with their dusty atmospheres and precarious towers of unshelved volumes, not knowing quite what it's like to catch a glimpse amid a crowded shelf of an unfamiliar book by a familiar author, extracting it with trembling hands, and then hoping that the store's owner won't suddenly decide to stop selling all these wonderful books before you got your new treasure to the register.

The teenager of tomorrow in possession of a Google Library Login ID will be able to download any Aldous Huxley book at any time and store it on the iThing for convenient reading. But why does this scenario seem so unlikely? Because selection becomes much more difficult when the options are unlimited? Because easy availability leads to contempt? Because having everything is the same as having nothing? Because it's much easier watching a video of a skateboarding dog on the iThing than reading a book?

Digital is disposable. So when the downloaded book is read, or partially read, or completely unread, and the time comes when new videos or new pop hits need the storage space, the iThing does what all digital devices do best: It deletes the unnecessary file from memory.

Poof! All gone. No more book — as if it had never even existed.

And so what? It's not as if the book means anything. It's not as if it's actually part of one's life.