Mahler 8th Not Awesome?

September 22, 2008

Roscoe, N.Y.

Early this year Raymond Chen published his annual Seattle Symphony season rundown, categorizing each piece with his one-word rating system including Awesome ("Guaranteed crowd-pleaser"), Nervous ("I have a bad feeling about this one"), and Polarizing ("Some people will love it; others will hate it").

Last year Raymond gave Gustav Mahler's 6th Symphony a Polarizing rating (which I took exception to) and this year Mahler's 8th Symphony — which will kick off the 2007/2008 season of the Seattle Symphony later this week — got the same treatment.

I'm sure Raymond's ratings are entirely empirical. I suspect that in the past some people have said "Yo Raymond! What's with this Mahler dude? Kinda loud, way too long, and then he makes me cry at the end." But I fear that some people who might actually enjoy the Mahler 8th could be scared away by the Polarizing characterization.

Mahler's 8th Symphony is big. Besides an augmented orchestra, the score calls for two mixed choirs, a boys' choir, eight vocal soloists, lots of percussion, harmonium, piano, two harps, and organ. Its inaugural performance in 1910 in Munich used just over a thousand performers. While most performances these days don't come close to that number, part of the fun of the Mahler 8th is seeing just how many people can be crammed on the stage of your favorite concert hall.

The first movement is a 25-minute setting of the Latin hymn "Veni, creator spiritus" ("Come, creative spirit"). It begins with a bang: a loud organ chord followed by the choir shouting out "Veni, veni, creator spiritus!" Yet the movement has many moods, at times getting very quiet and tranquil, and then building up to sections that hurtle forward with exhuberant abandon. Mahler dabbles with counterpoint and even fugue-like passages, almost resembling one of those raise-the-roof Baroque choral pieces (such as the Bach Magnificat, the Vivaldi Gloria, or Handel's Hallelujah chorus from Messiah). This first movement of the 8th Symphony is the most sustained expresssion of total joy to be found in all of Mahler.

The 8th Symphony has only two movements, but at about an hour in length, the second is Mahler's longest and perhaps his most ambitious. It is a setting of the last scene of Part II of Goethe's Faust. and the mood is very different from the first movement. It begins with an other-worldly sound — a soft cymbal together with the muted octave tremolo of the violins. Goethe's stage directions indicate "Mountain Gorges, Forest, Rocks, Desert" but the quiet plucking of the cello and basses accompanying a slow plaintive melody in the woodwinds puts us instead in a characteristically Mahlerian uncertain wilderness of the psyche.

When the choruses enter about 12 minutes into the movement, they almost chant the opening lines in a quiet breathless anticipation. The second movement rarely gets very fast. It maintains a stately, almost somber, pace with great — and I know this is a strange word to use regarding Mahler — restraint. Frequently the music seems to be on the verge of breaking loose, but Mahler holds back, building dramatic tension with some of the most beautiful combinations of voice and orchestra ever heard.

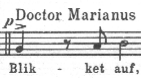

Close to the end, the tenor (singing the part of Dr. Marianus) introduces a simple three-note theme to the words "Blicket auf" ("Look up" or "Lift your eyes"):

(The key is E♭ major, so the A and B are flatted.) The organ is heard for the first time since the first movement, and soon the chorus and orchestra take up this new theme and, surprisingly, the initial "Veni, creator spiritus" theme.

The last chorus — “Alles Vergängliche / Ist nur ein Gleichnis” (“Everything perishable / Is merely an image”) — starts quietly accompanied only by the strings, and builds with great majesty. The "Veni, creator spirtus" theme enters again, much slower and this time sounding more profound for all that has happened in the interim. With the full orchestra and organ ablaze, everyone — orchestra, chorus, soloists, conductor, and audience — ascends into heaven.

Now if that's not Awesome, then the word Awesome has no meaning.

And if the word Awesome has no meaning, then how have we been communicating with each other for the past several decades?