Reading “The Better Angel: Walt Whitman in the Civil War”

Memorial Day, 2011

Roscoe, N.Y.

The sesquicentennial anniversary of the American Civil War has certainly increased the number of books coming out on the subject, but this has always been a healthy area of book publishing. Perhaps the big difference now is that people seem to be reading more of them. Of the several books I used in researching my blog entry on John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, perhaps the one most fascinating to me was Elizabeth R. Varon's Disunion! The Coming of the American Civil War, 1789-1859 (University of North Carolina Press, 2008) because it focused on the concept of the Union, which was originally somewhat amorphous until it became threatened by the conflict over slavery.

I tend to be most interested in books concerning the events leading up to the Civil War, and particularly the debate over slavery and abolitionism. Once the shooting starts and we move onto the battlefields, my mind wanders. Once recent exception to this rule was Drew Gilpin Faust's This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (Knopf, 2008), which was fascinating for its insights into how people back home dealt with so much death on the battlefield.

I also recently found Eric Foner's The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (W. W. Norton, 2010) to offer many insights into how the country and Lincoln himself evolved through the course of a war in their beliefs about slavery and what should be done about the slaves after the war ended. I was very pleased to see this book awarded a Pulitzer Prize for history.

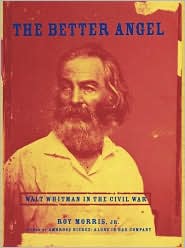

The Better Angel: Walt Whitman in the Civil War by Roy Morris, Jr. (Oxford University Press, 2000) has been sitting on my shelf for a decade begging to be read, and I finally did so. To be sure, this book offers an extremely idiosyncratic view of the American Civil War, but it's very well done.

When Lincoln was elected President in 1860, Walt Whitman was 41 years old. The first edition of Leaves of Grass had been self-pubished in 1855, but Whitman was now drifting. He lived with his mother and family in Brooklyn; he had on-again, off-again newspaper jobs; but he often spent his evenings at Pfaff's beer cellar, in Manhattan on Broadway near Bleecker Street.carousing with the other failed writers and artists who hung out there.

The onset of the Civil War in April 1861 seemed to give Whitman a well-needed jolt. He decided to clean up his life and eat healthier. His poems of this period exhibit a devoted patriotic spirit coupled with an idealistic vision of strong American soldiers marching to the rhythm of Whitman's powerful verses:

Eighteen Sixty-One

Arm'd year — year of the struggle,

No dainty rhymes or sentimental love verses for you terrible year,

Not you as some pale poetling seated at a desk lisping cadenzas piano,

But as a strong man erect, clothed in blue clothes, advancing, carrying rifle on your shoulder,

With well-gristled body and sunburnt face and hands, with a knife in the belt at your side,

As I heard you shouting loud, your sonorous voice ringing across the continent,

Your masculine voice O year, as rising amid the great cities,

Amid the men of Manhattan I saw you as one of the workmen, the dwellers in Manhattan,

Or with large steps crossing the prairies out of Illinois and Indiana,

Rapidly crossing the West with springy gait and descending the Alleghanies,

Or down from the great lakes or in Pennsylvania, or on deck along the Ohio river,

Or southward along the Tennessee or Cumberland rivers, or at Chattanooga on the mountain top,

Saw I your gait and saw I your sinewy limbs clothed in blue, bearing weapons, robust year,

Heard your determin'd voice launch'd forth again and again,

Year that suddenly sang by the mouths of the round-lipp'd cannon,

I repeat you, hurrying, crashing, sad, distracted year.

Like everyone else, Whitman never expected the war to last very long. He considered enlisting, but then changed his mind, probably for the best. His younger brother George enlisted in the 13th New York State Militia and later the 51st New York Volunteers. In December 1862, the New York Tribune included George on the list of casualties, and Walt headed to Washington D.C. to find him.

It turned out George was fine, but Walt found a calling that became the core of his Civil War experience. For many months, on and off, he would visit the wounded and dying soldiers in the military hospitals in Washington D.C., comforting them, giving them gifts, writing letters for them, and sometimes writing letters to their families after they had died.

This was not an easy life, and Whitman witnessed a great deal of suffering. Medicine was in a dismal state in the early 1860s. Almost nothing was known about germs and infection. Sanitary conditions were abominable. At least 100,000 soldiers died of diarrhea, and many more were afflicted with it. (Morris, pg. 84) Whitman once said that the war was "about nine hundred and ninety-nine parts diarrhea to one part glory." (Morris, pg. 171) Typhoid fever and malaria rounded out the most deadly killers. (Morris, pg. 91)

Rifles of the Civil War era tended to shoot bullets with rather low velocity, shattering bones and driving infection into the wounds. Amputation was the only real solution, despite being medically hazardous in itself. In one of Whitman's most powerful poems (apparently written in the late spring or early summer of 1863), he writes from the perspective of a wound-dresser making the rounds. Although Whitman did not actually perform this duty, it's obvious he watched others do it.

The Wound-Dresser (excerpts)

...

Bearing the bandages, water and sponge,

Straight and swift to my wounded I go,

Where they lie on the ground after the battle brought in,

Where their priceless blood reddens the grass the ground,

Or to the rows of the hospital tent, or under the roof'd hospital,

To the long rows of cots up and down each side I return,

To each and all one after another I draw near, not one do I miss,

An attendant follows holding a tray, he carries a refuse pail,

Soon to be fill'd with clotted rags and blood, emptied, and fill'd again.

I onward go, I stop,

With hinged knees and steady hand to dress wounds,

I am firm with each, the pangs are sharp yet unavoidable,

One turns to me his appealing eyes — poor boy! I never knew you,

Yet I think I could not refuse this moment to die for you, if that would save you.

...

On, on I go, (open doors of time! open hospital doors!)

The crush'd head I dress, (poor crazed hand tear not the bandage away,)

The neck of the cavalry-man with the bullet through and through examine,

Hard the breathing rattles, quite glazed already the eye, yet life struggles hard,

(Come sweet death! be persuaded O beautiful death!

In mercy come quickly.)

From the stump of the arm, the amputated hand,

I undo the clotted lint, remove the slough, wash off the matter and blood,

Back on his pillow the soldier bends with curv'd neck and side falling head,

His eyes are closed, his face is pale, he dares not look on the bloody stump,

And has not yet look'd on it.

I dress a wound in the side, deep, deep,

But a day or two more, for see the frame all wasted and sinking,

And the yellow-blue countenance see.

I dress the perforated shoulder, the foot with the bullet-wound,

Cleanse the one with a gnawing and putrid gangrene, so sickening, so offensive,

While the attendant stands behind aside me holding the tray and pail.

I am faithful, I do not give out,

The fractur'd thigh, the knee, the wound in the abdomen,

These and more I dress with impassive hand, (yet deep in my breast a fire, a burning flame.)

...

Whitman himself seems to have suffered post-traumatic stress disorder as a result of his long stints in the hospitals. But a trip back to Brooklyn revealed that his experiences with the soldiers "had 'veteranized' him to such an extent that he was now unfit for civilian life." (Morris, pg. 158) Although Whitman never actually witnessed a battle, his close interaction with the soldiers seems to have given him deep psychological insights into their traumas. Towards the end of the war, he wrote a quite amazing poem where he imagines himself to be a soldier many years later, awakened suddenly by what veterans of the Vietnam War called a "flashback":

The Artilleryman's Vision

While my wife at my side lies slumbering, and the wars are over long,

And my head on the pillow rests at home, and the vacant midnight passes,

And through the stillness, through the dark, I hear, just hear, the breath of my infant,

There in the room as I wake from sleep this vision presses upon me;

The engagement opens there and then in fantasy unreal,

The skirmishers begin, they crawl cautiously ahead, I hear the irregular snap! snap!

I hear the sounds of the different missiles, the short t-h-t! t-h-t! of the rifle-balls,

I see the shells exploding leaving small white clouds, I hear the great shells shrieking as they pass,

The grape like the hum and whirr of wind through the trees, (tumultuous now the contest rages,)

All the scenes at the batteries rise in detail before me again,

The crashing and smoking, the pride of the men in their pieces,

The chief-gunner ranges and sights his piece and selects a fuse of the right time,

After firing I see him lean aside and look eagerly off to note the effect;

Elsewhere I hear the cry of a regiment charging, (the young colonel leads himself this time with brandish'd sword,)

I see the gaps cut by the enemy's volleys, (quickly fill'd up, no delay,)

I breathe the suffocating smoke, then the flat clouds hover low concealing all;

Now a strange lull for a few seconds, not a shot fired on either side,

Then resumed the chaos louder than ever, with eager calls and orders of officers,

While from some distant part of the field the wind wafts to my ears a shout of applause, (some special success,)

And ever the sound of the cannon far or near, (rousing even in dreams a devilish exultation and all the old mad joy in the depths of my soul,)

And ever the hastening of infantry shifting positions, batteries, cavalry, moving hither and thither,

(The falling, dying, I heed not, the wounded dripping and red heed not, some to the rear are hobbling,)

Grime, heat, rush, aide-de-camps galloping by or on a full run,

With the patter of small arms, the warning s-s-t of the rifles, (these in my vision I hear or see,)

And bombs bursting in air, and at night the vari-color'd rockets.

Although Whitman despised the secession and its threat to the union, he nonetheless felt a great affinity with the soldiers of the south, and when they began pouring into Washington D.C. as the war was ending, Whitman offered them the same comforts as their northern brothers.

Whitman gathered many of his Civil War poems in a volume he called Drum-Taps, and he was in New York in the spring of 1865 overseeing the publication when word came that President Lincoln had been assassinated.

Like many Americans, Whitman was devastated by the news. He had seen Lincoln several times. The first time was in New York City when Lincoln was on his way to his first inaugural in the spring of 1861. Whitman also had some sightings of the President in Washington D.C., but always declined to try to speak to him, as if a little shy, reticent about interferring with the life of a man whose job, Whitman knew, was more important than his small role in the war.

Over the next months, Whitman wrote several elegies for President Lincoln for an addendum to Drum-Taps. From this period comes one of Whitman's best poems, "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd," with its references to the lilacs of that spring of 1865 as well as the presence of Venus in the evening hours. "O Captain! My Captain!" is a much shorter poem about a ship that successfully arrives in port but the Captain is now dead. This became perhaps the most popular of Whitman's poems, and he read it often in public long after he had ceased to think highly of it himself.

These elegies to President Lincoln in Drum-Taps conclude with a very short poem that almost seems innocuous until a startling bolt of anger in the third of its four lines:

This Dust Was Once the Man

This dust was once the man,

Gentle, plain, just and resolute, under whose cautious hand,

Against the foulest crime in history known in any land or age,

Was saved the Union of these States.

The war as well saved Whitman, and gave his life new purpose and meaning.