James Earl Jones Saves the Play

February 8, 2019

Sayreville, New Jersey

When I was 15 years old, my mother started letting me take the bus into New York City by myself. I would walk to the bus stop at the intersection of Route 9 and Ernston Road (at that time a traffic light), and after a 45-minute bus trip arrive at the Port Authority Bus Terminal. Usually I just went to bookstores but sometimes I saw a play, and that’s how I saw James Earl Jones onstage in The Great White Hope, and witnessed the great actor improvising a save when something unexpected threatened to blunt the play’s impact.

Howard Sackler’s play The Great White Hope is a fictionalized account of the boxer Jack Johnson, who in 1908 became the first black world heavyweight champion. In the play, he’s called Jack Jefferson. The ironic title refers to an attempt by white aficionados of the sport to find a white boxer who could beat him.

Prior to The Great White Hope, James Earl Jones had done some theater, television, and film (most notably Lt. Lothar Zogg in Dr. Strangelove), but this play was his breakout role. It opened in Washington D.C. in December 1967 with Jane Alexander in the role of Ellie Backman, a character based on Jack Johnson’s first wife, Etta Terry Duryea. The whole cast was then moved to Broadway, and according to the Internet Broadway Database, the play ran from October 3, 1968 to January 31, 1970, with Yaphet Kotto taking over the lead beginning September 8, 1969.

I probably first learned about the play from The New York Times. We didn’t get the daily Times delivered, but we got the Sunday edition for as long as I could remember. The play was widely acclaimed for his power and performances, and James Earl Jones at the age of 37 was suddenly a famous actor. Although I wasn’t a fan of boxing, the subject matter of the play — historical and yet relevant to contemporary politics and conflicts — certainly intrigued me.

I know I saw James Earl Jones on TV performing a scene from the play. That could very well have been the Ed Sullivan Show on February 2, 1969 (my 16th birthday!). I haven’t been able to find a video clip from that show, but YouTube has a 7-minute clip of Act 1 Scene 2 performed at the 1969 Tony Awards on April 20, 1969, and introduced by Diahann Carroll:

That’ll give you a good idea of the play’s language and rhythm, as well as Jones’ buffed up and physically imposing stage presence, with his head shaved and his skin oiled, and that now familiar deep booming voice. The Great White Hope won the Tony Award for best play that year (and the Pulitzer Prize for Drama), and James Earl Jones won for best leading actor, and Jane Alexander for best featured actress. (The 1969 Tony Award for best musical went to 1776, which I also saw on Broadway with my friend Eric.)

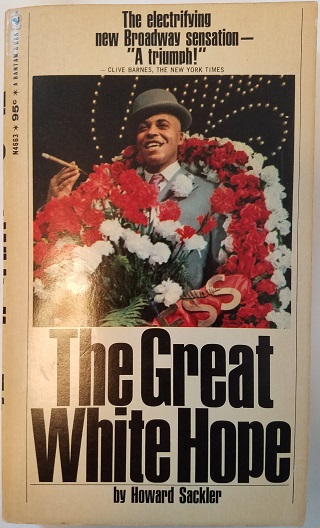

I was so interested in The Great White Hope that I bought a paperback of the play (shown above, with a publication date of April 1969) and read it. The first startling thing that the reader of the play discovers is that it’s written in blank verse. Of course, this influences the way that the actors read the lines, and the combination of this classic form and the often coarse language is ideal for the stage but much less suitable for the screen, as a later movie version of The Great White Hope demonstrated.

The characters very frequently break the fourth wall, so frequently that it’s typographically indicated: A little note at the beginning of the play instructs that “All lines set in boldface type are addressed to the audience.”

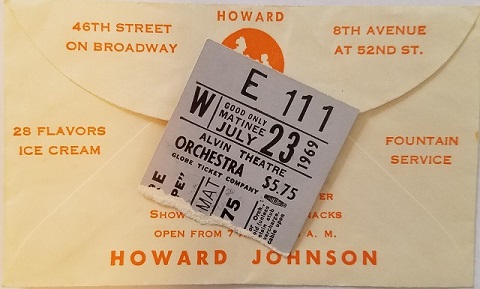

As I tried to determine when I saw The Great White Hope, I figured that it must have been the summer of 1969, the same summer as the moon landing (which of course I watched) and the Woodstock Music Festival (which didn’t interest me), and that it was probably June or July because later that summer we drove to Tucson to visit my grandparents. It was definitely a matinee.

And then, with a little searching, the playbill and my ticket stub turned up in a box of other playbills in a closet in my mother’s house:

I remembered sitting in the sixth row of the orchestra section, pretty close to the center, but the ticket stub is seat E111, which is usually the fifth row. Wednesday, July 23, 1969, was three days after the moon landing. The ticket cost $5.75. It’s possible I got the ticket earlier that day — also in the playbill was a crumbled ad ripped from the Times saying “You can see it NOW!” — and the seat might have been so good because it was a single.

Almost fifty years later, I can still visualize the stage and the people in front of me, and my 16-year-old self, mesmerized by the language and action of the play. Particularly if you’re seated close to the stage, theater has this special power of pulling you into the action, regardless how much you know that it’s all fake. At one point in Act 3, Scene 1, the character Clara (Jack’s former black girlfriend) begins blaming all their troubles on white people. She even points to some representatives of the race sitting close to the stage, and then she suddenly lunges for the people in the front row with her hands ready to strangle someone, and the other characters have to pull her back! Regardless how much you know rationally that the scene has been exhaustively rehearsed and performed day after day for over a year, it’s still quite shocking.

Sometimes, something happens in a theater that is not rehearsed, and the actors must save the play from the dangerously disruptive disturbance. Towards the end of The Great White Hope, in Act 3, Scene 3, Ellie (spoiler alert) commits suicide by throwing herself down a well, and Jack is stunned as three characters bring on stage Ellie’s “mud-smeared and dripping body.”

It’s a powerful scene, but in the performance that I saw, in a couple rows behind me, a teenage girl, or maybe two, giggled a bit, loud enough in a small theater for people to hear. I don’t know what triggered them to giggle. It surely wasn’t on purpose. But the giggles had the potential of emotionally muting the scene.

This is where a great actor — regardless of reciting lines that have been learned and repeated hundreds of times — can be so deep in the role that an improvisation can be second nature.

Keeping entirely in character, and using language that could very well have been part of the play, James Earl Jones quickly spun around and pointed his finger at the giggling girls. “You shut your face or I’m going to kick your ass too,” he bellowed.

Instant dead silence. A pause. As we were still reeling from this emotional punch delivered right to the audience, James Earl Jones turned back to the stage and resumed the play.