366 Deadlines: My Year with Beethoven

December 31, 2020

Sayreville, N.J.

On the first day of 2020 I announced an ambitious project to celebrate the 250th anniversary of the birth of Ludwig van Beethoven. Every day for the entire year, I’d post YouTube videos with commentary of all of Beethoven’s music in chronological order on the Twitter feed @beethoven250.

Today, on this last day of 2020, after 3800 tweets and 770 YouTube videos, that project is completed. The content of the Twitter feed has been transferred to the spanking new website The Complete Beethoven, which I hope will be a useful resource for anyone wishing to explore the entire range of Beethoven’s music. The Twitter feed will no longer be updated; I’ll do my best to maintain the website.

Anticipation and Reality

When I began this project, I thought that I’d be able to do it in my “spare time.” I should have known better! The big problem was that every day was a deadline. Every morning after I posted my prepared tweets, I’d often spend the rest of the morning and afternoon researching, selecting, and writing in preparation for the days ahead.

At the beginning of 2020, I wasn’t the only one planning to celebrate the Beethoven sestercentennial. I thought I’d be going to lots of concerts of Beethoven’s music during the course of the year, and I was particularly looking forward to seeing the Attacca Quartet perform all the String Quartets at Trinity Church, and a new production of Fidelio at the Metropolitan Opera. It occurred to me that I might publicize the Twitter feed at every concert of Beethoven’s music I’d be attending with a tee-shirt that read simply “@beethoven250” on the front and back. From such modest beginnings, viral Twitter feeds are born!

As it was, the last concert I went to was on March 6, 2020, and fortunately it was a good one: We had stage seating at Carnegie Hall for Emanuel Ax, Leonidas Kavakos, and Yo-Yo Ma in an all-Beethoven program: one Cello Sonata, one Violin Sonata, and a Piano Trio. After that, the only Beethoven I heard came through speakers, a poor substitute for live music.

In terms of standard social-media metrics, the @beethoven250 Twitter feed never did get much traction. I didn’t get 100 followers until mid-April. By the end of July I had 200 followers, and reached 300 on December 12. Beethoven’s actual 250th birthday gave me a boost, and I climbed to 400 over the next five days, but then it leveled off and ended the year this morning at 426.

The Reference Material

At no time did I feel myself academically qualified for this project. I have no formal education in music, and the only Beethoven I can play on the piano is the first page of “Für Elise.” It is true that my first published writings were reviews of classical music concerts for my college newspaper, but I am still insecure writing about music. I feel silly getting technical, and even sillier when indulging in rapturous prose.

I knew I needed a couple of books to help me out.

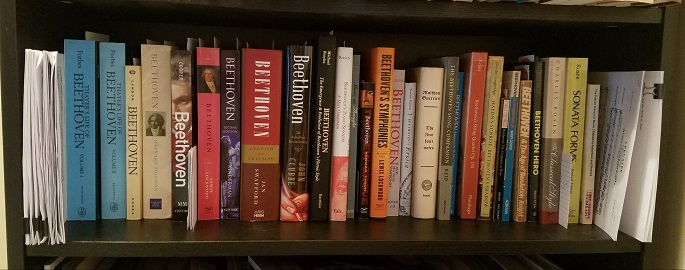

On February 17, 2020, I posted a photo on Facebook of my Beethoven bookshelf at that time:

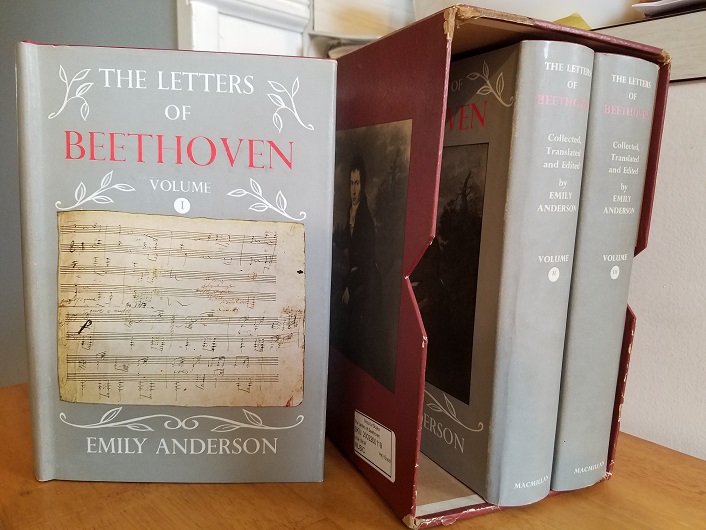

On April 29, I acquired a very special addition: the three volumes of Emily Anderson’s translations of Beethoven letters:

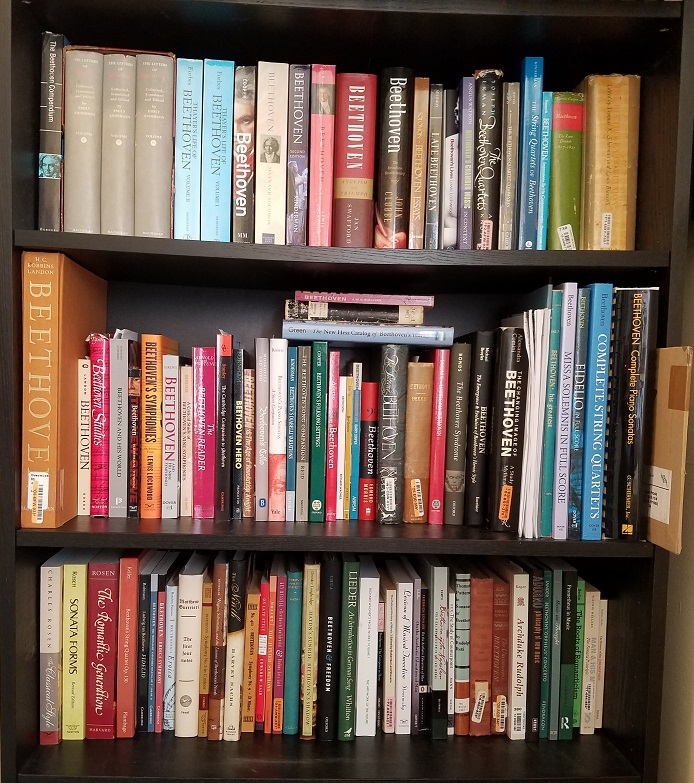

By the end of 2020, the Beethoven (and related) shelves looked like this, except never quite this neat:

But that quantity of books is obviously overkill for my modest purposes. Out of sheer lack of time, I wasn’t able to use many of those additional books, though I dipped into them all at one time or another.

Over the course of 2020, I read the following seven biographies in parallel, always keeping a year or two ahead of where I was in the Beethoven chronology:

In my Twitter commentary on Beethoven’s life and music, I quoted from all these biographies.

If anyone ever asks me for a recommendation of a Beethoven biography, I’d hem and haw a bit (just for show), but then suggest Lockwood for the best combination of Beethoven’s life and musical analysis.

Thayer-Forbes (as it’s called) is essential for anyone doing research on Beethoven. All the other biographies cite it. Alexander Wheelock Thayer was able to interview many people who had known Beethoven, and he was the first Beethoven biographer to establish a fact-based non-mythological approach to his subject. The edition by Elliot Forbes has numerous corrections, revisions, and additions. But it’s too much detail for most readers, and it doesn’t delve at all into the experience of hearing the music.

Barry Cooper’s book was essential to me for its obsessiveness about chronology, and it’s a good second choice behind Lockwood. I love Maynard Solomon’s psychological insights, even when they reach beyond what’s deducible from the facts. But I didn’t like how he separated the biographical details from his discussions of the music, which are relegated to just four chapters entitled “The Music.”

I think Kinderman tends to be too technical for many people. I became annoyed at Clubbe’s agenda and some of his errors. Swafford is eminently quotable, and his descriptions of Beethoven’s music are fresh and unusual and often insightful. But it always seems as if he’s extrapolating a step or two beyond what the facts warrant.

For its index alone, Jan Swafford’s book deserves particular scorn. Unlike all the other biographies I used, Swafford’s doesn’t have a separate index for the music. The main index incorporates the music but in a disastrous manner. Only a sadist or a moron would construct an index so that the five piano concertos are alphabetized as “Piano Concerto No. 1,” “Piano Concerto No. 2,” “Concerto No. 3,” “Fourth Piano Concerto,” and “Emperor Concerto.” Finding the String Quartets in the index is even worse unless you know who they were dedicated to and what their nicknames were.

Although all the biographers often quote Beethoven’s letters, I feel I got a much better portrait of Beethoven from reading the unabridged assemblage:

Because I got Emily Anderson’s book somewhat late in the process, I can’t claim to have read it all, but I consumed much of the 2nd and 3rd volumes.

Several other general books about Beethoven were useful in various ways:

I thought this large-format paperback would be more useful than it turned out to be:

It’s good for a quick reference for various aspects of Beethoven’s life, but the essay sections seemed too broad.

The following 200-page monster is a treasure, with many old and more recent descriptions of Beethoven’s compositions. Despite its ridiculous organization, it’s chock full of wonderful nuggets that would be hard to find elsewhere:

The following book is a classic of sorts, a wonderful compendium of 39 reminiscences:

I wish the following book weren’t so disorganized, but it’s great for numerous illustrations, including all the known portraits of Beethoven during his lifetime as well as many of the major people in his life This is the giant hardcover edition:

There’s also an abridged paperback published by Collier Books.

For more information on the symphonies, I consulted:

For chamber music in general, I loved this book:

For the string quartets, I consulted:

However, the third one in that list proved to be rather too academically inclined for my purposes.

For the chamber music with cello, I got a lot out of:

For the piano sonatas, I always wished I had some more books, but Charles Rosen’s was certainly useful, despite being more oriented to the performer rather than the listener:

I have several books that focus on individual works, but this one deserves a special callout:

And this one is a real hoot:

For the lieder, I would have been totally lost without this essential book:

Similarly for the folksong settings:

One of the last Beethoven-related books I purchased during the year was this one, which I got specifically for information concerning the late canons:

That book, as well as several of others in this list, was purchased from the once-robust Beethoven shelf in the basement of the Strand Book Store, a bookstore I’ve been shopping at since high school, and whose vicinity to my New York City apartment was a primary reason I moved there.

If I had to do it all over again, I’d definitely invest in Theodore Albrecht’s three volumes of letters to Beethoven, as well as the recent edition of Kinsky-Halm. And I’d prepare by spending a year or two learning more German than what I acquired from three years instruction in an American public high school, which left me functionally illiterate in the language.

Several online sources were exceptionally useful. The International Music Score Library Project is an enormous collection of downloadable scores:

That page shows an alphabetical list, but for a list by Opus and WoO numbers and more, click:

Another link in my Favorites Bar was that of the Beethoven-Haus museum in Bonn:

Use the listbox in the upper-left column to find a particular work by Opus or WoO number. Sometimes there’s just a date of composition, but often more.

The

site sometimes provided essential information. I used

quite often, as well as

Typing a couple search terms in JSTOR’s search box often turned up interesting scholarly papers. For periodicals that are not available on JSTOR, fortunately I am a resident of New York City and hence have access to the “Scan and Deliver” service of the

Of course, let us never ever forget the greatest website ever:

How the Sausage was Made

Not every composer can accomodate a schedule of one work per day for a year. Haydn wrote far too many compositions; Mahler wrote far too few.

But Beethoven seemed just about right. His completed works are catalogued with 138 Opus numbers (some of which encompass multiple compositions) and about 200 WoO numbers, so the total seemed to come close to the number of days in the year. But I knew I couldn’t proceed haphazardly. I needed a plan and a list.

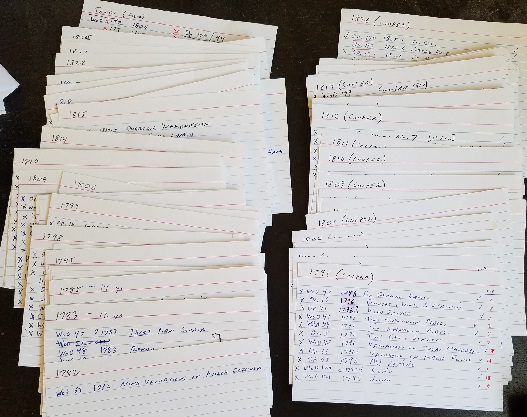

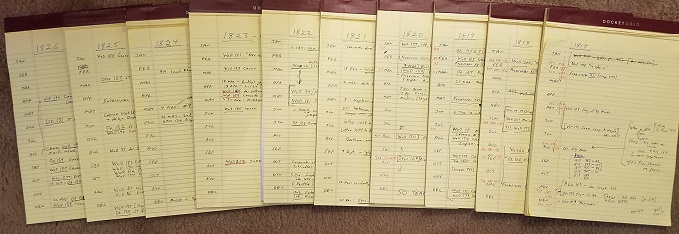

I began the preparation for the Beethoven 250 project in November and December 2019 using an Excel spreadsheet to list every Beethoven composition in chronological order. At first, Thayer-Forbes seemed ideal. The book’s chapters are organized by year, and at the end of each chapter is a list of compositions completed during that year, so I manually transferred those lists into an Excel spreadsheet grouped by year. Then, suspecting that the Thayer-Forbes chronology was probably not up to date with modern scholarship, I assembled a deck of 4 × 6 cards, one per year, and listed the compositions in each year from the back of The New Grove Beethoven.

By about mid-February, I was dissatisfied with that chronology as well and I decided to place (almost) full faith in the chronology in Appendix B of Barry Cooper’s Beethoven (2nd edition). I assembled another set of 4 × 6 cards. I kept both decks and chronicled progress by checking off the works as they were posted.

I also scanned and printed the 16 pages of Barry Cooper’s Appendix B, so I could check off works as they were posted to make sure I hadn’t missed anything.

Throughout the project, the Excel spreadsheet remained the core list of compositions. As each year in Beethoven’s life approached, I would fine tune the chronological arrangement for that year in the spreadsheet, organizing the works as they were described in the pages of Barry Cooper’s biography, supplemented with other sources. I could then begin searching for YouTube videos, the https://www.charlespetzold.com/blog/2020/12/366-Deadlines-My-Year-with-Beethoven.htmls of which I would save in the spreadsheet along with the composition. I’d generally accumulate about half a dozen https://www.charlespetzold.com/blog/2020/12/366-Deadlines-My-Year-with-Beethoven.htmls (if available) and then determine which video or videos I would post.

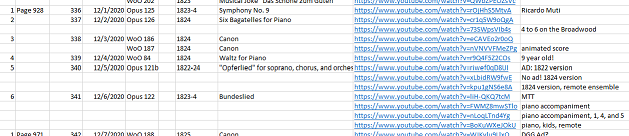

Despite all the changes, the Excel spreadsheet retained the remnants of its Thayer-Forbes origins. Here’s the block showing the year 1824. Page 928 is the page in Thayer-Forbes that lists the 1824 compositions. Each composition was numbered within each year, and then cumulatively through the year, along with the date:

Later on in the year, I made another Excel spreadsheet solely for the folksong settings. I was able to sort this one based on either the published Opus or WoO number, or the Cooper Folksong Setting group and number, which corresponded to compositional chronology.

The precise numbering of the remaining compositions in the year was inexact until late November. Only then could I determine what I would be posting on each day in the final month of December. The tiny canons that are prevalent in Beethoven’s later years became conveniently “elastic": I could double up the canons on a day, or devote an entire day to just one canon to make the total come out to exactly 366.

I composed the tweets for each day in Word. With a short program I first generated a text file with the following text for each day of the year 2020:

Day 1: Wednesday, January 1, 2020

#Beethoven250 Day 1

and so forth. I imported that text file into Word, and using search and replace made the lines beginning with “Day” a heading. The other line of text would form the first line of a tweet to post the YouTube video.

For each composition on each day, I would read what the authors of the biographies and other books had to say about it, and then strive for a combination of my own impressions, and those of actual Beethoven scholars. As I assembled the Twitter posts for each day in the Word document, I’d make frequent use of the Review | Word Count option to check for the 280-character limit. These daily tweets generally became more numerous as the year progressed.

Twitter was probably not the best medium for this project, but I don’t know of an alternative that has the same high visibility. The big problem is that followers don’t necessarily see every tweet you post. Unless tweets are chained, every tweet needs to stand on its own. When discussing compositions, I found myself beginning each tweet with a phrase such as “The final movement of Beethoven’s Violin Sonata No. 8 ...” so that the subject matter of the tweet is completely identified without the surrounding tweets.

Every morning, I would cut-and-paste the tweets for that day into Twitter, often making small edits in the process. This was one of the first things I would do in the morning, often before a shower or beverage. Because there was no real emotional investment in this largely mechanical job, it would not register well in my mind. Often I would experience a little panic later on in the day that I had forgotten to do it.

If I knew I had something to do that might take up much of a day, I had to get ahead a day or two in selecting the videos and composing the tweets. If I took a day off (for instance to read a novel), then I’d be struggling to catch up. I don’t think I ever got more than three days ahead. We were originally supposed to spend two weeks during the summer in Mexico with iffy Internet access, and I began researching how I could automate the daily posting of tweets, but I never had to resort to that. I had access to my computer every day of the year.

To further assist in organization and planning, I began using yellow pads for each year of Beethoven’s life, taking notes from the various biographies I was reading to assemble a more detailed monthly chronology:

Other pages in each yellow pad would be devoted to the compositions of that year, sometimes two pages for major compositions, and consolidating minor compositions in a single page.

In the last couple weeks of the year, I used a yellow pad for each String Quartet, with different pages for notes from each reference source.

Curating the Videos

For each composition, I would try to find a variety of performances on YouTube. I’d store the https://www.charlespetzold.com/blog/2020/12/366-Deadlines-My-Year-with-Beethoven.htmls in the Excel spreadsheet, and add notes as I watched each video. Then I would attempt to choose among them using a variety of criteria.

YouTube videos of classical music fall into two distinct categories:

I have been buying and listening to recordings of classical music for over 50 years, and I appreciate that recordings have made music much more accessible than in the 19th century. However, there’s a tendency in studio recordings to eliminate all mistakes and create a “perfect” performance. In one sense, this is necessary because a mistake in a recorded performance effectively becomes louder and louder each time that recording is played.

But by eliminating anything that might suggest that actual human beings are playing the instruments, recordings conceal the essential physicality of music-making. Live performances often include anxiety, sweat, horn flubs, spit dumped from brass instruments, broken strings, violin squeaks, page turnings, and audience noise. To me, this physicality is an essential part of music performance.

Prior to recordings, every performance of a particular work was different, and this too is an important component of music performance. I am well aware that recording connoisseurs often worship at the shrines of certain conductors, singers, and other musicians from decades gone by, but I don’t like the way that those recordings become embedded in our heads as an ideal that can never be surpassed. I recoil at the concept of a “definitive” or “perfect” performance.

For these reasons, I wanted my Beethoven 250 project to focus on live performances. That was my overwhelming criterion for selecting YouTube videos. Of course, watching a video is nowhere close to the experience of attending a live concert, but it’s as close as we can get through this medium. Only when there were no live performances available would I resort to a YouTube video of a ripped recording. In those cases, I favored those that included animated scores.

In choosing among live performances, I tended to favor young musicians in recent performances because they are the ones who make this music continually fresh and alive, and who will carry it into the future.

It used to be — and not so long ago! — that orchestras and string quartets consisted entirely of Caucasian males. Certainly they made lots of good music. But I kept remembering Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s response when asked how many women should be on the Supreme Court. “Nine,” she would say. “For most of this country’s history, there were nine and they were all men. Nobody thought that was strange.”

Hence, I will not apologize that I often selected performances not dominated by Caucasian males.

From Twitter to HTML

I realized early on that while it might be appropriate to use Twitter for a project in which I’d be posting every day, it wouldn’t work well for a permanent archive. There’s even a limit how far you can page back in a Twitter feed! I knew I would eventually want to transfer all the posts from my Twitter feed to a website.

Fortunately, this is possible. Twitter has a facility to download your feed and all the data associated with it. From the · · · item on the menu list, select Settings and privacy and then Download an archive of your data. Within 24 hours, you’ll get a notification that it’s ready. Then you have to wait 30 days to do it again. (The facility was disabled for a couple months during the summer as a response to a Twitter attack.)

The Twitter archive comes in the form of a Zip file. For me, the final one was 26 megabytes in size. It contains a bunch of files, including all the images you may have posted and a JSON file named tweet.js, containing all your tweets. My year-end tweet.js was 4 megs long. It was fairly straightforward to write a C# console program to convert the tweets and links to HTML. Any corrections I needed to make to the tweets I had to hard-code in the program, or accumulate in a correction list that the program would apply.

Towards the end of the year, I decided I needed something a little more flexible, and I split the program in two: The first part read the JSON with the Twitter feed and converted it all to a simplified Markdown file, which turned out to be a megabyte in size. The second program generates the entire Complete Beethoven website from the Markdown file. This allows me to make hand changes to the Markdown (which I’ve been doing a lot in the past couple days), or to redesign the HTML pages.

Discoveries

When I began this project, I was familiar with the standard Beethoven repertoire. I knew Fidelio, the symphonies, piano concertos, violin concerto, overtures, string quartets, piano sonatas, violin sonatas, cello sonatas, and some of the other chamber music, but much of the joy of this project was exploring this music chronologically and systematically; listening to it intently (often with the benefit of the score) so I could attempt to comment intelligently; and discovering the more obscure compositions.

Beethoven occupied a unique position in music history. As a youngster he met Mozart, and he later studied with Haydn, yet by the end of his life he was influencing Berlioz and Schubert. In straddling the Classical and Romantic eras, Beethoven’s music exemplifies the sea change during this period, some of which he influenced and some of which influenced him. The way his music evolves over the decades is astonishing. Experiencing that evolution over the course of 2020 was both enlightening and exciting.

It is common to divide Beethoven’s life into three periods. Yet, when you’re proceeding chronologically through Beethoven’s music, it’s hard to detect the boundaries. Beethoven makes certain artistic leaps at some points, but then tends to move back a little, so the progress becomes a ragged continuum. But progress there is, and it is thrilling to go along for the ride.

I found myself getting interested in odd aspects of Beethoven’s music. In the 1790s, Beethoven wrote a bunch of piano variations based on arias from operas that have long since fallen through the cracks of music history. I wanted to know more about those obscure operas, and sometimes I was able to find out.

Before I got to the 179 folksong settings from 1809 to 1820, I fretted a lot about what I would do about them. But the more I searched YouTube, the more live performances turned up, and I was able to include YouTube videos of live performances of 77 of them.

Towards the last couple years of Beethoven’s life, I became inordinately interested in the little canons and other short pieces of music that he wrote in letters and as souvenirs to visitors. I wanted to know more about the circumstances of each of these pieces. Sometimes that information is not available, but often it is, and it provides a little snapshot of a moment in Beethoven’s life when in lieu of signing an autograph or saying something witty in a letter, he composes a few bars of music.

As 2020 progressed, more and more “isolation videos” or “quarantine videos” began showing up on YouTube. People were performing the music of Beethoven alone in their homes or synchronized with others. Sometimes these performances are tinged with sadness — such as when the choir of the Technical University of Munich joins online to sing Beethoven’s setting of “Auld Lang Syne” (Day 312) — or to compensate for a missed concert opportunity — such as when Hannah De Priest sings from a kitchen (Day 318) — or when the circumstances spark an inventive idea for a unique performance, such as when Sasha Cooke sings “An die ferne Geliebte” (Day 294) in progressively more challenging and then silly settings.

This is when we realize how resilient Beethoven’s music is, and how resilient are the musicians who love this music and who cannot be stopped from performing it, even when that essential interaction of a live audience is temporarily suspended.

Beethoven’s first 250 years are just the beginning.