Elder Care

April 6, 2021

Roscoe, N.Y.

In February, my mother, Barbara Petzold, celebrated her 95th birthday on Zoom with her three children, four grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren. A month later, she died in her sleep in the house she lived in since 1954. By her choice, no blinking lights, beeping machines, wires, tubes, or strangers accompanied her death, only members of her family.

My mother was born in St. Louis, and also grew up in Little Rock and Oklahoma City. She was an only child. Both her parents were graduates of the University of Kansas, and her father was an engineer for the Bell System. Although my mother lived through the Great Depression, her father remained employed, and the only deprivations she remembered involved putting cardboard in her shoes when the soles wore worn.

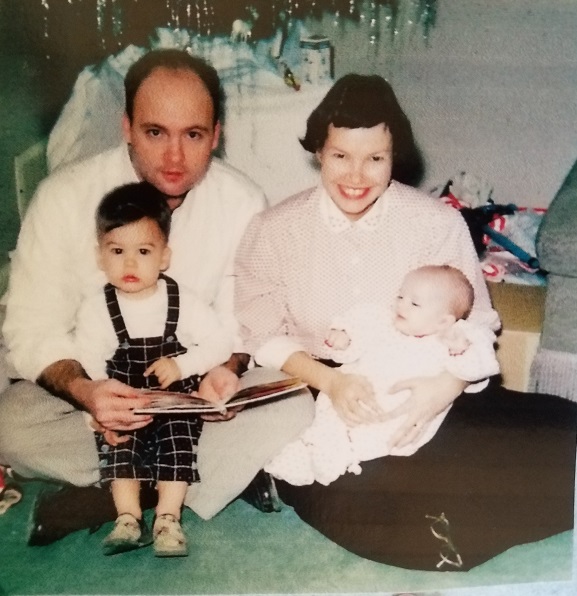

She attended the University of Missouri where she met my father, a veteran of WW II who was going to college on the G.I. Bill. They married in 1950. In 1954, when I was one year old, they bought a new house in Sayreville, New Jersey, for $12,900. My brother Steve was born later that year. This is the first Christmas in the new house:

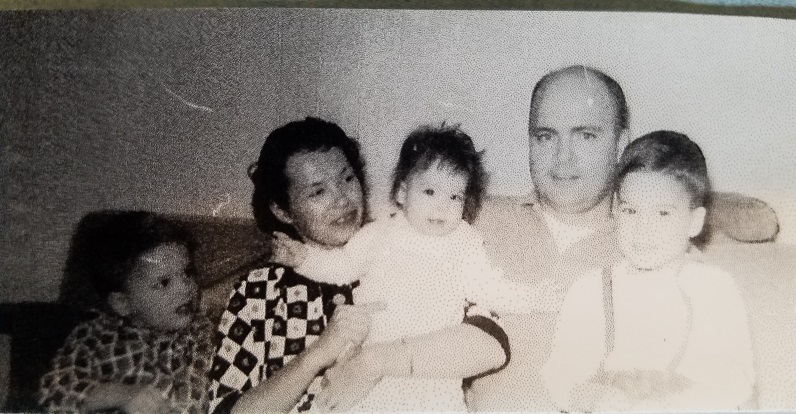

My sister Sue followed a few years later:

The fairly idyllic life my mother led to that time ended very suddenly after just ten years of marriage when my father was killed in a commercial aircraft disaster. I was seven, my brother was six, and my sister was two. My mother was left to raise us on her own. Over the next decades she would discover an inner strength that allowed her to survive this trauma and adversity, and to triumph in raising a family under extraordinary misfortune.

After my father’s death, we survived largely on Social Security survivor benefits, but I never had the sense of being poor. My mother’s single-minded devotion was to ensure the best possible future for her three children. If that had meant remarrying, I’m sure she would have. If it meant protecting us from potentially abusive stepfathers, then that was also a factor. As it was, she was courted by at least three widowers in the neighborhood, none of whom met her high standards. Several years later I was astonished to see one of them quite accurately depicted on TV in the form of Archie Bunker.

My mother had been raised with a strong moral sense. This example comes to mind: One of my brother’s male teachers (a bachelor) solicited my mother to help chaperone a class trip. She discovered only after showing up that she was the only mother so invited. Moreover, this teacher had forged a letter from the school’s principal saying that the kids were emotionally disturbed. They couldn’t tolerate standing in long lines, so the letter suggested that they be allowed to cut in front of everyone else. If this teacher believed that this ploy would impress my mother, he was seriously mistaken. She was appalled at this and other cases of dishonesty or deception.

My mother always had high expectations for her children. There was never any question that we would all be going to college. I remember one of the other mothers in the neighborhood yelling at her kids for reading too much because it would ruin their eyes. My mother never discouraged reading, and in particular allowed my reading to go in quite unconventional directions. And yet, she also maintained that crucial balance between her expectations for us and an acceptance of her children’s individuality and independence.

After her three children had all graduated college and left that little house in Sayreville, my mother lived by herself for over three decades. As she got older and frailer, she had to give up her car, and my sister would help with grocery shopping and appointments with doctors.

In January 2018, my mother had a stroke. We celebrated her 92nd birthday in a hospital, and we visited her frequently in a sub-acute rehab center where they focused on physical and speech therapy. By this time, she was using a walker. She had to drink thickened liquids, and her speech also suffered from aphasia.

After that stroke, it was obvious that my mother would no longer be able to live by herself. We considered several options before my wife Deirdre and I decided to move into her house so she wouldn’t have to move out. We purchased some essentials — an Ikea bed with drawers underneath, a wide desk, bookcases — and moved into the bedroom where my brother and I once shared a bunkbed that my father built. Deirdre set up her office space in my sister’s old room with a desk and computer.

We didn’t know how long we’d be living with my mother and her two cats in New Jersey. We thought we’d try a month and see what happened. It continued long beyond what we had anticipated. It was in that house where I spend my last working days before retirement and where Deirdre completed her first novel, The Third Mrs Galway.

I doubt there is much that is unique in our situation: As parents increasingly live much longer lives, elder care will become a more common experience for us offspring who are ourselves no longer young. Elder care is giving back the care we received when we were much younger. Although my experience was not nearly as challenging as what my mother faced as a single parent, it was still hard, and I could not have done it on my own. I will be forever thankful to Deirdre’s gracious help for sharing this experience with me.

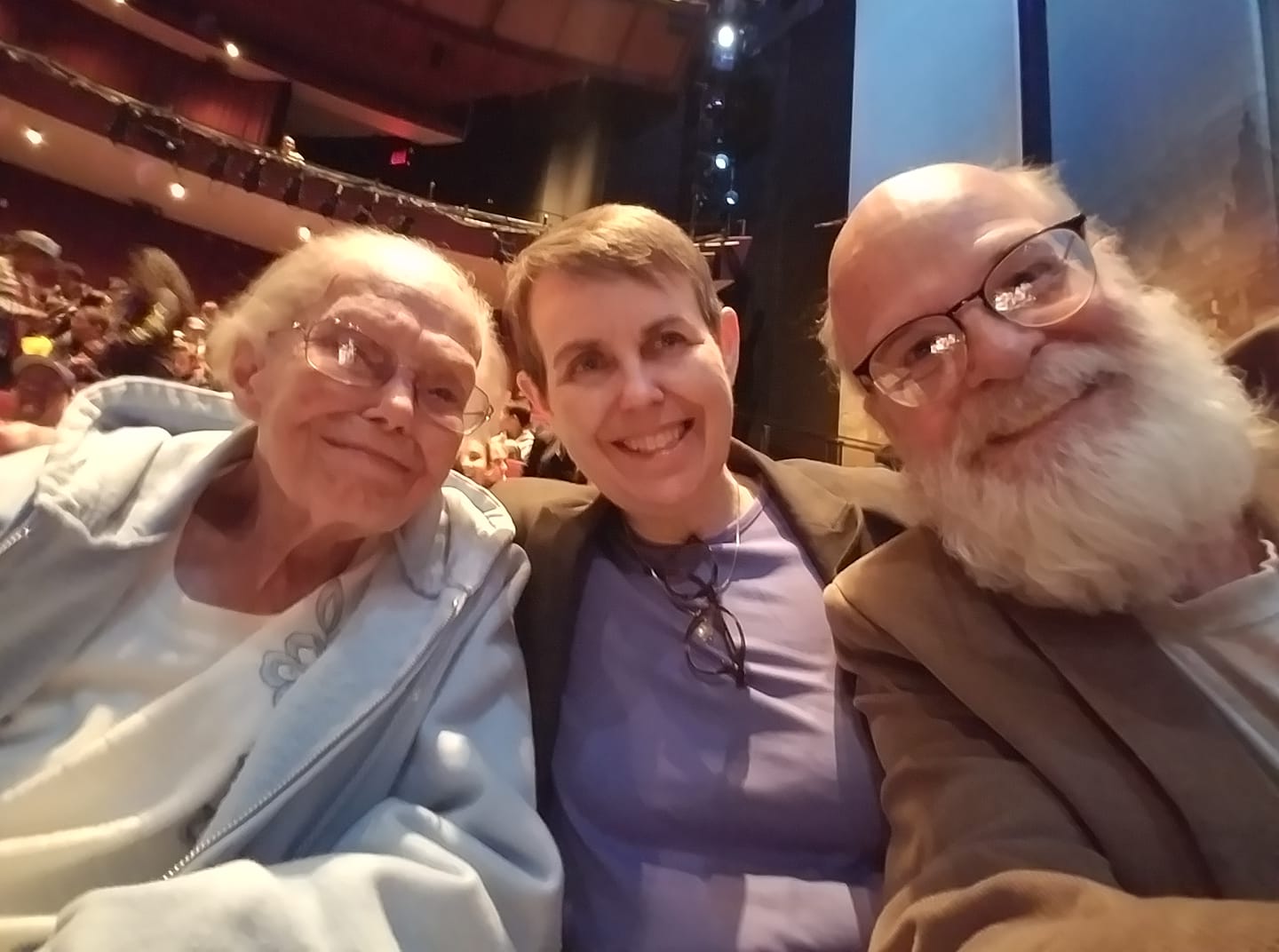

For the first two years of caring for my mother, we were able to take her to restaurants and movie theaters, and to continue a tradition I began in 1977 by taking her to see a Broadway musical every year. Here’s my mother, Deirdre, and me in April 2019 with front-row seats for My Fair Lady at the Vivian Beaumont Theatre.

That was the last musical we saw. We had tickets for Wicked last year but it was cancelled by Covid. Virtually all outdoor excursions with my mother ground to a halt. The primary objective of elder care shifted to keep her safe from this nasty virus, and in that we were successful. We also realized that the alternative to at-home elder care — putting my mother in a nursing home — would likely have been disastrous.

It has oft been observed that several aspects of elder care are similar to baby care, and that old people age as rapidly as the young. For me, the worst part of my mother’s decline was witnessing her deteriorating eyesight. Even after her stroke, she could still read her beloved police procedurals by J. D. Robb and Heather Graham, but reading got more and more difficult. She moved from large-print books to a Kindle and then back to large-print books with a magnifier, until finally she gave up. For her daily doses of Jeopardy and Wheel of Fortune — perhaps the most universal part of elder care — we replaced her TV with a much larger screen, and put it on a stand that we could move closer to her chair. She’d still occasionally guess a Wheel puzzle before the contestants, and sometimes shouted out a Jeopardy question. On the weekends, we’d try to find a TV series or movie she might enjoy. We still have a list of those we didn’t get to.

Perhaps the strangest ritual was something Deirdre began doing. My mother liked to know when famous people died, so every morning Deirdre would read aloud select obituaries from that morning’s New York Times. I’m not sure if it pleased my mother more to learn that she outlived someone, or if people could get even older than her.

Before her stroke (and until her arthritis and eyesight became issues), my mother’s primary hobby was assembling room boxes with 1:12 scale miniature furniture and often populated by several cats. She left behind numerous room boxes everywhere in her house. My favorite was on the wall above the toilet in her bathroom: a much more glamorous bathroom than her own but with one of the cats drinking out of the bowl.

One of my jobs following my mother’s death was decommissioning the computers she used for email. Her first computer was an original Bondi Blue iMac that I gave her. I had purchased it when they first went on sale in August 1998 because I was working on my book Code and wanted to familiarize myself with the Mac to make sure that I wasn’t saying anything in the book that was PC-specific. In November 2002, I replaced my mother’s first iMac with an iMac G4 (the ones with the distinctive dome base) so she could maneuver the display closer to her already failing eyes. She used that one for thirteen years until early 2016 when I got her a Mac Mini connected to a larger monitor on a swivel arm attached to her desk. She used that right up until her stroke.

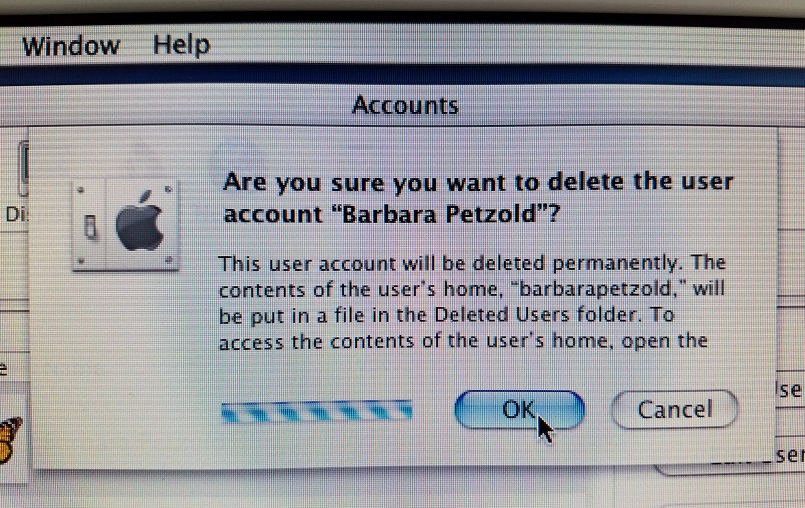

It was the iMac G4 that was most challenging to decommission. I did my best to preserve the 13 years of email correspondence, but I didn’t have her passcode so I needed to jump through hoops to wipe the hard drive, one step of which involved removing her user account. The message box displayed during this process was particularly poignant in context:

Seeing that weird message, and considering how much a part of my mother’s later life was preserved in those email messages, I got to thinking about our relationship with our electronic appliances.

Just 25 days before my mother died, Kazuo Ishiguro’s new novel Klara and the Sun came in the mail. Sitting on the couch near my mother’s chair in her living room, I opened the book and started reading aloud. I hadn’t planned to, but once I started I just continued, for four hours that day and then lesser stretches over the next three days until I finished.

It was normal for me to read novels aloud in the car while Deirdre drove, so my mother heard several over the years, particularly as we drove her to and from our little house in the Catskills. But Klara and the Sun was the last she heard, and while it might have been a little odd for her — a novel narrated by a humanoid Artificial Friend — she seemed to get something out of it.

In Klara and the Sun, Ishiguro doesn’t give the reader much information about the company that manufactured the Artificial Friends and the engineers who designed them. But those designers seem to have given some thought to what would happen to these AFs after they were no longer needed. They experience a type of sundown period. From our perspective, it seems somewhat crass: Klara is confined to a junkyard among piles of other recycled electronics, still conscious as she sits almost motionless, left along with her thoughts. But being privy to Klara’s thoughts, we know she’s at peace. “I like this spot,” she says. “And I have my memories to go through and place in the right order.”

We hope in our hearts that dying humans have that same peacefulness: that they are aware that they are free from worries, beyond any need for responsibility. Of course we don’t know. We can’t see into the minds of other people. We barely know our own minds. What’s mostly left behind by the dead are their creations — room boxes as well as emails — and the memories of the survivors.

In any novel about artificial intelligence, the question arises about the differences between them and us. Klara herself seems to believe that there is nothing special in humans that can’t be mimicked by AIs. But an earlier search in the novel for something special in her human friend Josie was misguided: “There was something very special, but it wasn’t inside Josie. It was inside those who loved her.”

The ostensible purpose of elder care is to allow the later years of our loved ones to be as comfortable and as rewarding as possible. But elder care goes both ways: It becomes as rewarding and indispensable for us giving the care as for those who receive it.