Witnessing the Gestation of “The Third Mrs. Galway”

July 10, 2021

Roscoe, N.Y.

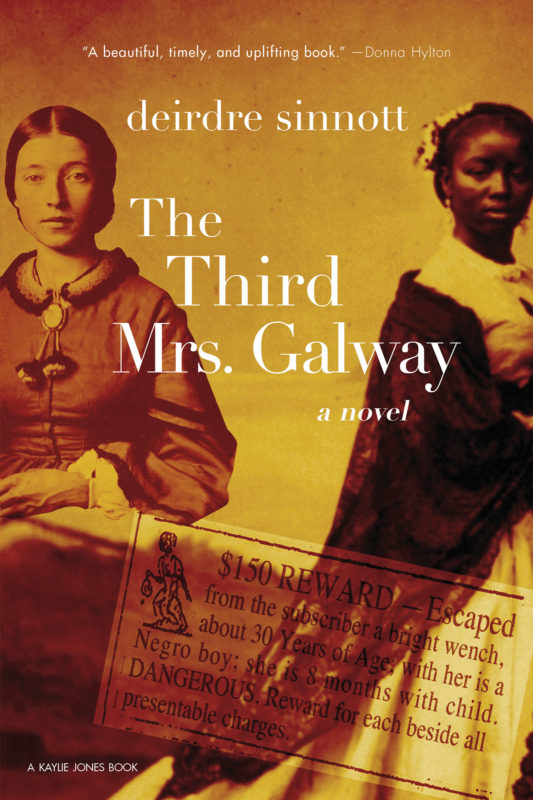

I’ve read a bunch of novels, but The Third Mrs. Galway is the first one whose gestation I witnessed, and that’s because my wife Deirdre Sinnott wrote it. It’s her first novel, and the official publication date was Tuesday, July 6, 2021. Congratulations!

It was a long gestation. For decades, Deirdre had been interested in early 19th century anti-slavery activity in upstate New York and particularly her hometown of Utica. In 2007, she discovered that something quite significant had happened there: On October 21, 1835, the founding meeting of the New York Anti-Slavery Society was disrupted by a mob opposed to the radical concept of the abolition of slavery. Deirdre did a considerable amount of research into this event, became one of the experts on it, and delivered some talks about it.

Around 2015, an idea for a novel occurred to her that might use this founding meeting and the riot as a backdrop. At one point, in reading some period newspapers from that period, she discovered that something else also going on during that time was the 1835 return of Halley’s Comet.

“You have to put that in the novel,” I told her. “In earlier times, comets were often viewed as omens of tumultuous events, and that’s what’s happening here.” I paused dramatically (as I recall), and said: “In fact, there’s your title: The Comet.”

Well, that didn’t happen. But I suggested she read John Pringle Nichol’s 1837 book Views of the Architecture of the Heavens in a Series of Letters to a Lady for some insights into how learned people viewed astronomy during that period. That eventually led to one of the many marvelous scenes in the novel, in which people gather in a park to view Halley’s Comet through a telescope. One of the main characters expounds on the nature of the universe in the language of natural theology — somewhat foreign to our ways of thinking but perfectly suited to the period.

That was my most significant contribution to The Third Mrs. Galway, which is available from its publisher Akashic Books as well as many real and virtual bookstores, including Bookshop.org, McNally Jackson, the Oneida County History Center, Barnes & Noble, and Amazon, where you can also get the Audible audiobook, or directly from Audible.

Except for several flashbacks and a brief coda near the end, The Third Mrs. Galway takes place entirely in Utica, New York, in October 1835. This was a quarter century before the conflict over the institution of slavery would erupt into the Civil War, but not very long after slavery had been abolished in New York State. But that story is rather complicated:

In 1799, New York became one of the last of the northeast states to pass a law abolishing slavery. Like the other northeastern states, this was to be a gradual process. The Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery stipulated was that anyone born of an enslaved mother after July 4, 1799, would be indentured to the mother’s owner until the age of 28 for males or 25 for females. Only after reaching that age would they would be entirely free.

The law said nothing about enslaved people born prior to July 4, 1799. Another law passed in 1817 freed those enslaved people, but not until July 4, 1827. That’s the date commonly celebrated as the end of slavery in New York State, but even afterwards, there were apparently some people born after 1799 who were still serving their periods of indentureship.

Regardless of the tardiness of New York’s emancipation, in the decades thereafter, New York became one of the centers of anti-slavery activism. But the debate didn’t divide cleanly into two opposite camps. Many prominent New Yorkers (and other Americans) did not believe that slavery should be abolished immediately. A popular alternative was colonization, which involved shipping freed Black people to a colony in Liberia on the West African coast. This approach particularly appealed to people who believed slavery to be morally wrong but who were wary of integrating free Black people into American society. (Keep in mind also that the memory of Nat Turner’s Rebellion was still fresh.) Although colonization later proved to be a disaster, that didn’t stop its advocates from believing that abolition was a threat to the fabric of the country.

The Third Mrs. Galway captures the richness of the historical debate over slavery, but historical novels need to balance the history and the personal, and in the foreground of Deirdre’s novel is a very personal story that gets much more personal as the novel proceeds:

A young woman — recently married to an older man of high social status — discovers in her backyard shed a pregnant woman and her ten-year-old son fleeing slavery. She’s doesn’t know what to do. She’s been taught that slavery is generally a benevolent institution, her husband is a member of the Colonization Society, and moreover, the slavecatchers are knocking at the door and offering rewards.

It’s easy for us to tell her “Help them, of course!” but keep in mind that it was illegal. Embedded in the United States Constitution was a provision for for the interstate retrieval of people “held to Service or Labour.” Also in effect at this time was the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, which punished those who “shall harbor or conceal such person after notice that he or she was a fugitive from labor.” In 1835, helping people escape slavery was morally equivalent to helping someone break out of prison. It was prohibited by law and convention, and dangerous besides. Most people just wouldn’t risk it.

Through scrupulous historical detail and a dazzling array of real and fictional characters, Deirdre plunges us into the moral conflicts of the era, and the emotional conflicts of attempting to do the right thing, even if it’s not clear what that is.

And that applies not only to 1835. It remains a perennial challenge.