Reading “Humanly Possible”

August 11, 2023

Roscoe, N.Y.

When some Facebook friends recently began posting prose and poetry generated by ChatGPT, I had an odd reaction. I didn’t feel astonished, or amused, or intrigued, or frightened, or threatened. (Well, maybe a little.) Mostly I felt disgusted. I felt that I was witnessing a travesty of human creativity, a mockery of human communication, and a belittling of human morality.

Most everything that we humans do or say has consequences in this world. When we speak or write, the intent is to convey information or change someone’s mind, which means that the content of our speech or writing cannot exist in an ethical vacuum. Every sentence has ethical implications within a moral framework that is formed through a lifetime of experience of interacting with other people with whom we feel kinship and empathy as fellow humans.

The big problem with chatbot software is that it’s stringing words and sentences together based on statistical inferences rather than an understanding of the meaning of the words and phrases. It doesn’t know what it’s doing. We humans generally take personal responsibility for what we write and say, but a chatbot is fabricating prose without any sense of moral responsibility. The chatbot has no skin in the game (literally!), and without this moral underpinning, the output of a chatbot must be regarded as gibberish, despite how meaningful it might seem.

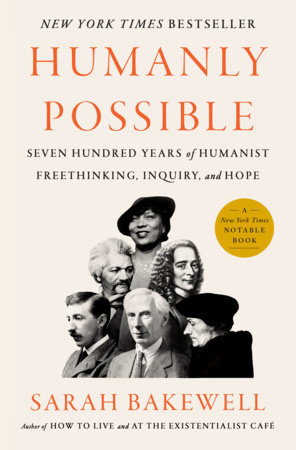

I felt I was having a particularly humanist response to this technology, so I was more eager than ever to read Sarah Bakewell’s ambitious and enlightening survey of humanism, Humanly Possible: Seven Hundred Years of Humanist Freethinking, Inquiry, and Hope (Penguin Press, 2023)

The first challenge in a book about humanism is defining what on earth it is. Some hints are suggested by the portraits on the cover, but identifying the common characteristics among Zora Neale Hurston, Frederick Douglass, Voltaire, E. M. Forster, Bertrand Russell, and Desiderius Erasmus might be even more challenging than a verbal definition.

Bakewell confronts the problem of definition in both the book’s Introduction and an Appendix, which includes the Declaration of Modern Humanism from Humanists International. You can consult that on your own, but that organization’s Minimum Statement on Humanism might help us get oriented:

“Humanism is a democratic and ethical life stance, which affirms that human beings have the right and responsibility to give meaning and shape to their own lives. It stands for the building of a more humane society through an ethic based on human and other natural values in the spirit of reason and free inquiry through human capabilities. It is not theistic, and it does not accept supernatural views of reality.”

That last part is problematic for some people, and in some countries, anti-blasphemy laws effectively make humanism illegal.

Bakewell concludes the Introduction with her own definition of humanism, which relies on the three words in her subtitle:

Freethinking: because humanists of many kinds prefer to guide their lives by their own moral conscience, or by evidence, or by their social or political responsibilities to others, rather than by dogmas justified solely by reference to authority.

Inquiry: because humanists believe in study and education, and try to practice critical reasoning, which they apply to sacred texts and to any other sources set up as being beyond question.

And Hope: because humanists feel that, failings notwithstanding, it is humanly possible for us to achieve worthwhile things during our brief existence on Earth, whether in literature or art or historical research, or in the furthering of scientific knowledge, or in improving the well-being of ourselves and other human beings. (p. 22)

The remainder of the book consists of numerous profiles and anecdotes of humanists throughout history in the context of social, historical and philosophical movements. A comprehensive history of humanism would encompass many more than Bakewell’s 400 pages, so her book is necessarily a very personal and idiosyncratic journey. This is ideal, for Bakewell’s book could never be mistaken for anything that was generated by a chatbot. It is a delight to read, filled with humor, and Bakewell really knows how to stretch out a joke: A comment about knickers on page 60 is referenced on page 261.

Bakewell’s survey of humanists is roughly chronological and begins with 14th century bibliophiles such as Petrarch and Boccaccio, who rediscovered the Latin prose of Cicero and the poetry of Virgil. But that word “bibliophile” doesn’t quite convey the intensity of their love. These guys were book crazy. If they came across a book that they needed to have but couldn’t cart away, they would copy it by hand.

Books were crucial for reminding medieval readers that people once thought profound thoughts. In the 15th century, the first-century Epicurean poem by Lucretius, On the Nature of Things, was rediscovered by Poggio Bracciolini and began an influential dissemination throughout Europe. (This is a story told in Stephen Greenblatt’s The Swerve: How the World Became Modern.) A new humanist handwriting developed to facilitate the writing, reading, and copying of books (p. 66), and that handwriting became the basis of new fonts for printing presses. The earliest surviving book to come off an Italian printing press was Cicero’s De oratore. (p. 80)

One of the heroes of Bakewell’s book is Lorenzo Valla, a fearless fifteenth-century Italian scholar who pioneered textual analysis with the intent of probing seemingly authoritative documents. His big accomplishment was demonstrating that a Roman decree entitled Donation of Constantine was a forgery. But this was not just an academic exercise: The decree had been used to justify the dominion of the Pope over all of western Europe. Another of his projects was identifying errors in Jerome’s Latin translation of the Bible, which was used extensively within the Roman Church.

But it’s not only writers who are humanists. Chapter 4 of Humanly Possible is devoted to medicine, and as Bakewell notes, “Mitigating the suffering of one’s fellows is a humanistic goal in the broadest sense, and in general the practice of medicine straddles the worlds of science and humanistic study.” (p. 122)

If humanism implies lessening manmade suffering, then the horrors of war are also a humanistic concern. Bakewell emphasizes this in her extended discussion of Desiderius Erasmus:

What he hated above all was war. Already before the Reformation, he had used his In Praise of Folly to describe war as a monster, a wild beast, and a plague. In his 1515 Adages, he included a long entry discussing a saying by Vegetius: Dolce bellum inexpertis — three neat Latin words that come out more laboriously in English as “War is sweet to those who have not experienced it.” Here and in his 1517 Complaint of Peace, Erasmus set out reasons to avoid war. The most fundamental one is that, in his view, it contradicts our true humanity, which we should be striving to develop and fulfill. (pp. 149–50)

Although Erasmus was initially sympathetic to the cause of Reformation espoused by Martin Luther, he was repelled by Luther’s aggressiveness, and Bakewell correctly identifies the outcome of the contentious theological battle that Luther helped trigger:

Centuries of intermittent, bloody wars, complicated by political struggles, would shatter communities and bring suffering, most of it to people who would not normally expect to have their lives affected greatly by theology at all. Erasmus, and his later admirers and followers, spoke up against such destruction where they could, but usually found they could do little to prevent it from happening. (p. 148)

And here’s Erasmus himself:

How much more truly Christian it would be to have done with quarrelling and for each man cheerfully to offer what he can to the common stock and to accept with good will what is offered! (p. 148)

All of which makes me want to read one of the more massive volumes on my “hope-to-read-but-who-am-I-kidding shelf”: Michael Massing’s Fatal Discord: Erasmus, Luther, and the Fight for the Western Mind — alas, some 800 pages before the endnotes.

Another humanist who lived through those wars sparked by the Protestant Reformation is Michel de Montaigne, about whom Sarah Bakewell has written an earlier book whose idiosyncrasy is indicated by the title How to Live, or A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer. Montaigne too was opposed to massacre and homicide, as well as the common practice of burning heretics and witches. It was, he said “putting a very high price on one’s conjectures to have a man roasted alive because of them.” (p. 155)

Some anti-humanists today identify humanism as a type of atheistic religion. The problem with this is that the humanists that Bakewell discusses in the first 40% of her book are believers, even though sometimes unorthodox and skeptical ones. Another problem is that when Bakewell does discuss misguided attempts at humanistic religions — such as Auguste Comte’s Religion of Humanity and the New Humanism of Irving Babbit — they are clearly not the same as her other examples.

Once we get to the Enlightenment, however, the influence of religion begins its historical decline. Even that widespread 18th century belief of deism — the idea that the universe was created but that the creator no longer takes any interest in this creation — had humanistic implications:

If prayer and ritual do not matter, and if nothing happens outside the general order of nature, then our lives are entirely human concerns. What we lose in personal attention and miracles, we gain in the benefits of being responsible for our world, and able to improve things if we want to without any comment from above.

The results for ethics are dramatic. If we want to live in a well-regulated, peaceful society, then we must create one and maintain it. Instead of referring moral questions to divine commandments, we must also work out our own system of good, generous, mutually beneficial ethics. We can try to generate our own rules — such as “do as you would be done by,” or “treat all human beings as an end in themselves, not a means to something else,” or “choose the action that brings the greatest happiness to the greatest number.” These are handy tools for moral thinking, but they are not the same as a set of orders literally set in stone tablets by God. Our moral lives remain complex and personal — and human.

Humanists and Enlighteners were thus drawn to an old idea: that the best foundation for this human, moral world lies in our spontaneous tendency to respond to one another with fellow feeling: “sympathy,” or empathy, or the sense of interrelatedness expressed by ren or ubuntu. It is what Condorcet called “a delicate and generous sensibility which nature has implanted in the hearts of all and whose flowering waits only upon the favorable influence of enlightenment and freedom.” (pp. 173–4)

Bakewell devotes a nice eight pages to David Hume (pp 186–194) as a refutation of the idea “that an irreligious person could not be a good person.” But at this point, I started to feel as if I were in the company of old friends. Many of the people who exemplify humanism for Bakewell have also been the subjects of this blog, including Spinoza, Davis Hume, Denis Diderot, Henry Fielding, and Mary Wollstonecraft. Voltaire shows up towards the end of the first chapter of one of my books-in-progress.

In this blog I’ve also discussed humanists from the 19th and 20th centuries, including some six entries on Anthony Trollope, who is apparently my favorites author, and George Eliot, who wrote my favorite novel, Middlemarch. That blog entry on George Eliot also discusses books that she translated by two of Bakewell’s subjects, David Friedrich Strauss (pp. 269–70) and Ludwig Feuerbach (pp. 272–73).

I’ve written blog entries on John Stuart Mill, who Bakewell quotes as advocating a liberal society that supports “absolute freedom of opinion and sentiment on all subjects, practical or speculative, scientific, moral, or theological” (p. 233), Frederick Douglass, and Charles Darwin:

Darwin’s explanation for morality is a thoroughly humanistic one: it emerges from social feelings and behavior, and need not rely on anything coming from God. If anything, he sees the process as operating in the reverse direction: he speculates that, at some later stage of culture development, the general moral gaze of others becomes identified with an imagined figure: that of “an all-seeing Deity.” (p. 256)

Bakewell credits “Darwin’s Bulldog,” Thomas Henry Huxley for another significant development in humanism:

As a zoologist, an educator, and an eloquent essayist and polemicist, he would do more than anyone else in that period to promote Darwinism, and, in the process, to bring together two great nineteenth-century currents: the boom in education and free-thinking, and the turn toward science-based ways of thinking about ourselves. He thus inaugurated a new type: the scientific humanist. (p. 250)

T.H. Huxley also coined that useful word “agnosticism” (pp. 256–7), literally meaning “no knowledge” — a belief that the question of the existence of God is beyond human experience and reasoning. When Bertrand Russell — who makes an important appearance in Chapter 3 of my book The Annotated Turing — was arrested for antiwar activities in 1918, Bakewell notes:

On arrival at the prison gate, he had to give his details to the warder. “He asked my religion, and I replied ‘agnostic.’ He asked how to spell it, and remarked with a sign: ‘Well, there are many religions, but I suppose they all worship the same God.’” (p. 297)

Russell’s antiwar activism spanned half a century:

Bertrand Russell continued to be a stalwart of the anti-nuclear campaign, writing about it and taking part in demonstrations for the rest of his life. After one such occasion in 1961, when he spoke to a crowd in London’s Hyde Park, he was convicted of “inciting the public to civil disobedience” and sentenced to a week in Brixton Prison. He was now eighty-nine years old. The magistrate did try to let him off in exchange for a promise of “good behavior,” but Russell would promise no such thing. Like Voltaire, he became only more fearless and provocative as he went on in life. (p. 339)

I also seem to have written about a few other 20th century humanists who Bakewell discusses in her book: E. M. Forster, Thomas Mann, and Kurt Vonnegut.

But in Humanly Possible, Sarah Bakewell cites many more who I know only by name, and others that I’m ashamed not to know at all, including the Jewish Ukrainian author Vasily Grossman, whose book Life and Fate, written during the Stalin and Khrushchev regimes, was almost destroyed by the KGB but managed to survive and become published and translated:

There are certainly lots of copies of Life and Fate around today. If someone asks you “What is humanism?” and a more direct answer does not come to mind, you could do worse than taking that person to a bookstore and buying them one. (p. 362)

OK then! Another 800+ page book for the to-read shelf!

In the last several pages of Humanly Possible, Bakewell devotes not nearly enough space to the implications of technology. She cites Jaron Lanier’s You Are Not a Gadget and George Eliot’s “Shadows of the Coming Race” (which I discuss towards the end of my blog entry “The Lesser-Read George Eliot”), as well as — again, much too briefly — posthumanism and transhumanism. But perhaps these are awkward subjects not quite appropriate for a book that celebrates humanism in all its myriad forms.

Humanism seems so basic and fundamental that it also seems as if it should be universal. Yet we are constantly reminded that it’s simply not so. Dictatorships and theocracies are only the most blatant enemies of humanism. Others are much more subtle and insidious.