Rereading Aldous Huxley’s “Point Counter Point” and “Devils of Loudun”

September 12, 2023

New York, N.Y.

When I was a teenager, I was an Aldous Huxley “completist.” I didn’t know that word at the time. It was not in common use. But I exhibited all the symptoms: After being blown away by a reading of Brave New World at the tender age of 14, I thought the author’s genius probably wasn’t limited to just one book, so I began an obsessive search for Huxley’s other works. Most of the novels were readily available, but I didn’t stop there. Fortunately I grew up just a 45-minute bus ride from New York City, and when I was 15, my mother started letting me take that bus by myself. I would visit the used bookstores on the famous (but now merely a fond memory) Book Row where I found many of Aldous Huxley’s collections of essays, short stories, travelogues, and yes, even poetry, all of which I ravenously read.

I still own all these books that I bought over 50 years ago. Here’s my Aldous Huxley Shelf as I photographed it 16 years ago for my passionate defense of physical books, “Our Books, Our Selves”:

The books are doubled up for shelving efficiency; paperbacks of the eleven novels are in the front at the far right in compulsively chronological order. (My collection does not include the six volumes of Aldous Huxley’s Complete Essays published between 2000 and 2002. My obsession was long over by that time.)

To quote myself from that earlier blog entry:

I think what impressed me most about Huxley was that he seemed to know about everything. Science, literature, art, music, philosophy, religion, history — this was a level of learning and knowledge clearly beyond anything I could hope for from the public schools of New Jersey. I felt it was necessary to supplement my formal education with reading, and part of this plan involved reading more Huxley.

What I also found interesting is that Huxley went through several intellectual evolutions over his lifetime, some of which (such as a commitment to pacifism) had a profound influence on me, while others (his interest in mysticism) ultimately left me cold. What teenager wants to be an ascetic? But I liked the idea of this evolution, and that one’s education could continue over a lifetime and result in different manifestations of interest and belief.

I recently reread two of the Huxley books I had the fondest memories of, probably for the first time since the 1970s. I didn’t only read them, however; I read them aloud in my capacity as human audiobook riding shotgun in our car while my wife Deirdre drives.

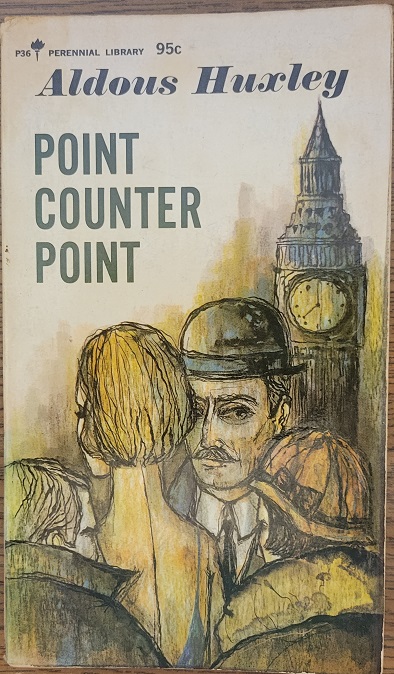

Aldous Huxley’s fourth novel, Point Counter Point, published in 1928 four years before Brave New World, is generally considered to be his best. I first read it (and more than once) as this 95¢ paperback:

I also have something that purports to be a first edition of Point Counter Point that I bought for 75¢ on Book Row, but it was published by the Literary Guild of America (at the time recently created to compete with the Book of the Month Club), so it doesn’t really count as a first edition. For this reread, I bought a recent edition published by Dalkey Archive Press,

As the title Point Counter Point suggests, it was Huxley’s intent to apply a musical structure to this novel, with characters flowing in and out of different relationships with each other. In a kind of meta-commentary on Huxley’s intentions, Point Counter Point includes the ruminations of Huxley’s fictional stand-in, Philip Quarles, as he writes in his notebook:

The musicalization of fiction. Not in the symbolist way, by subordinating sense to sound. (Pleuvent les bleus baisers des astres taciturnes. Mere glossolalia.) But on a large scale, in the construction. Meditate on Beethoven. The changes of moods, the abrupt transitions. (Majesty alternating with a joke, for example, in the first movement of the B flat major Quartet. Comedy suddenly hinting at prodigious and tragic solemnities in the scherzo of the C sharp minor Quartet.) More interesting still, the modulations, not merely from one key to another, but from mood to mood. A theme is state, then developed, pushed out of shape, imperceptibly deformed, until, though still recognizably the same, it has become quite different. In sets of variations the process is carried a step further. Those incredible Diabelli variations, for example. The whole range of thought and feeling, yet all in organic relation to a ridiculous little waltz tune. Get this into a novel. But how? The abrupt transitions are easy enough. All you need is a sufficiency of characters and parallel, contrapuntal plots. (pp. 293–4)

And then he continues with some examples. Whether Huxley was successful accomplishing something radically different in Point Counter Point is doubtful. Without this idea being suggested to the reader, the interweaving of various characters and plots wouldn’t seem to be much different from Middlemarch or Anthony Trollope’s long novels. (And keep in mind that James Joyce’s Ulysses had already been published six years earlier.)

This passage also exhibits Huxley’s casual erudition. Some day — my teenage self would muse — I would understand every allusion in a Huxley novel! Reality check: No way! I had to use Google Book Search to find the source of that French quotation. (It’s from “Nocturne” by Stuart Merrill, an American poet who often wrote in French.) The three Beethoven compositions are not nearly as obscure, although I suspect that even Huxley’s musically literate readers might not have been fluent enough to know offhand the particular movements of those two String Quartets. In contrast, the mention of the Diabelli Variations provides a comparatively easy reference point.

Some readers don’t like cultural allusions. They feel that authors are showing off or demonstrating that they’re better educated than their readers. But I knew Huxley was a lot smarter than me, and although I aspired to be as much of a cultured intellectual as Huxley, I never came close. I don’t know French or Latin, and what jumped out at me in this rereading ot Point Counter Point were unnervingly frequent allusions to something or somebody named Sodoma:

Page 62: “There was something in his smile, Mrs. Betterton reflected, that reminded one of Leonardo or a Sodoma — something mysterious, subtle, inward.”

Page 63: “He made an effort and smiled his Sodoma smile.”

Page 125: “giving her one of his grave and subtle Sodoma smiles”

Page 126: “glancing up at her with a sudden mischievous, gutter-snipish grin, most startlingly unlike the Sodoma smile of a moment before”

Page 231: “He came round the table to meet them, smiling his subtlest and most spiritual Sodoma smile.”

Page 235: “He smiled a Sodoma smile, subtle, spiritual, and sweet”

Page 352: “smiled down at him with the wistful, enigmatic tenderness of one of Sodoma’s saints.”

Fortunately there is now Wikipedia, from which I learned that Il Sodoma is the Renaissance painter Giovanni Antonio Bazzi, and perhaps the enigmatic “smile” refers to a self-portrait that appears in one of his paintings:

Here’s a rather perplexing musical allusion. The conductor Tolley was introduced in Chapter 2:

At the Queen’s Hall Tolley began with Erik Satie’s Borborygmes Symphoniques. Philip found the joke only moderately good. A section of the audience improved it, however, by hissing and booing. (p. 392)

Although the author of an article on music in Point Counter Point in a 1977 issue of Studies in the Novel devoted to this novel seems to believe that this was a real Satie composition, it’s obviously just a lame spoof of that eternal bugaboo, “modern music” — in this case, music based on stomach growlings. This silly joke hasn’t aged well: To more modern readers, Satie’s works are considered charming and proto-minimalist, while some compositions of Schoenberg, Berg, and Bartók — all known during the era of Point Counter Point — are still considered too modern for many coddled ears.

Point Counter Point is also a “novel of ideas,” a concept also explored by Philip Quarles in his notebooks:

Novel of ideas. The character of each personage must be implied, as far as possible, in the ideas of which he is the mouthpiece. In so far as theories are rationalizations of sentiments, instincts, dispositions of soul, this is feasible. The chief defect of the novel of ideas is that you must write about people who have ideas to express — which excludes all but about .01 per cent. of the human race. Hence the real, the congenital novelists don’t write such books. But then, I never pretended to be a congenital novelist. (pp. 294–5)

As a novel of idea, Point Counter Point is not as nearly as extreme as what I remember of Eyeless in Gaza (1936) or After Many a Summer (1939) or his utopian novel Island (1962) published 30 years after the dystopian one. But a good part of the novel does involve people sitting around arguing.

Mark Rampion — whose character and ideas are usually identified with D. H. Lawrence — comes off as the hero of the novel. He urges us to live life fully, to not become a slave to any kind of one-sided “perverted” life, be it political or economic, scientific or religious. Yet his monologues are often little more than extended rants:

“[T]he only truth that can be of any interest to us, or that we can know, is a human truth. And to discover that, you must look for it with the whole being, not with a specialized part of it. What the scientists are trying to get at is non-human truth. Not that they can ever completely succeed; for not even a scientist can completely cease to be human. But they can go some way toward abstracting themselves from the human world of reality. By torturing their brains they can get a faint notion of the universe as it would seem if looked at through non-human eyes. What with their quantum theory, wave mechanics, relativity, and all the rest of it, they do really seem to have got a little way outside humanity. Well, what’s the devil’s the good of that?”

“Apart from the fun of the thing,” said Philip, “the good may be some astonishing practical discovery, like the secret of disintegrating the atom and the liberation of endless supplies of energy.”

“And the consequent reduction of human beings to absolute imbecility and absolute subservience to their machines,” jeered Rampion. “I know your paradises. But the point for the moment is truth. This non-human truth that the scientists are trying to get at with their intellects — it’s utterly irrelevant to ordinary human living. Our truth, the relevant human truth, is something you discover by living — living completely, with the whole man….”

This stuff goes on for pages. And yet, we never get a good idea of what Rampion’s ideal life is all about, other than being somewhat more rounded than the ideal of a well-rounded human being. What’s interesting is that the Rampions seem to have the best marital relationship in Point Counter Point. Everybody else (even Philip and Elinor Quarles) are having sexual affairs or aspiring to them.

Besides occasional mentions of music and composers, Point Counter Point is bookended by two extended descriptions of music compositions. In Chapter 2, it’s Bach’s Suite in B minor, also known as the Orchestral Suite No. 2, BWV 1067. In the final chapter, it’s the central movement of Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 15 in A minor (opus 132), the movement that Beethoven entitled Heiliger Dankgesang eines Genesenen an die Gottheit, in der Lydischen Tonart — the holy song of thanksgiving of a convalescent to God, in the Lydian Mode, which one of the characters considers to be a proof of the existence of God.

While reading these two sections aloud in the car, I was able to pop in the appropriate CDs and cue them in synchronization with Huxley’s descriptions. Back in my high school days, I yearned to hear this music, but I could not. Where I grew up in New Jersey, it was simply not possible to go into a record store and buy an LP of the music of Bach or Beethoven. The culture (so to speak) did not allow it, and dire consequences would likely result. Instead, I’d scour the listings in the Sunday New York Times of music scheduled for the upcoming week on WQXR, which was then the radio station of that newspaper. It was only when I got to college that I had the freedom to buy classical LPs.

Being a little more knowledgeable of history and politics now than when I was a teenager, I was particularly interested in the character of Everard Webley, who runs an organization called The Brotherhood of British Freemen. Although the word “fascist” is not used to describe his political orientation, Webley is described as a “Tinpot Mussolini” (p. 40), so the implication is clear. He exhibits all the trappings of fascism but delivers somewhat populist speeches that could appeal to the disaffected. But Point Counter Point was published in 1928 — four years before Oswald Mosley founded the British Union of Fascists.

At one point Philip Quarles muses to himself that:

At different times in his life and even at the same moment he had filled the most various moulds. He had been a cynic and a mystic, a humanitarian and also a contemptuous misanthrope… (pp. 193–4)

It seems to be the misanthropic side of Huxley/Quarles that emerges from this novel. As a youngster, I understood it to be a satire of a certain slice of English life circa 1928, but in the recent reading, I found it cruel and nasty. All the men (to quote Elinor Quarles) are “Pigs” (p. 288) with the exception of Mark Rampion, who is insufferable in his own way.

The women of Point Counter Point are largely a void. It has been widely understood that Huxley drew upon his artistic and literary circle to form the characters of this novel, so that Lucy Tantamount was influenced by Nancy Cunard (with whom Huxley had an affair). But Nancy Cunard was a writer, a publisher, and a political activist. Lucy is a shallow aristocrat, and her writing is restricted to increasingly discouraging letters to Walter Bidlake.

Walter Bidlake’s mother, Mrs. Bidlake, is supposedly inspired by Ottoline Morrell, yet we feel nothing of what made Morrell so vital to many writers and artists. Beatrice is based on artist Dorothy Brett, and yet Beatrice doesn’t paint. This was an era in English life when strong women were pursuing their own writing or artistic careers or becoming focal points within artistic circles, and yet the women in Point Counter Point are consistently thinly drawn.

Are there any likeable characters in Point Counter Point? Not really, but I’m not someone who requires likeable or identifiable characters in novels or movies. I’ve had that attitude for a long time, and I now wonder if this trait might have resulted from an early immersion in this very novel.

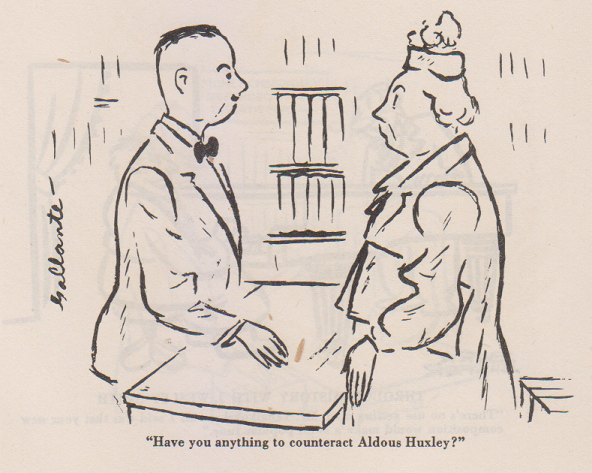

Originally appeared in the Saturday Review of Literature, Vol. 22 (1940);

reprinted in Laughs from the Saturday Review of Literature (Vanguard Press, 1946)

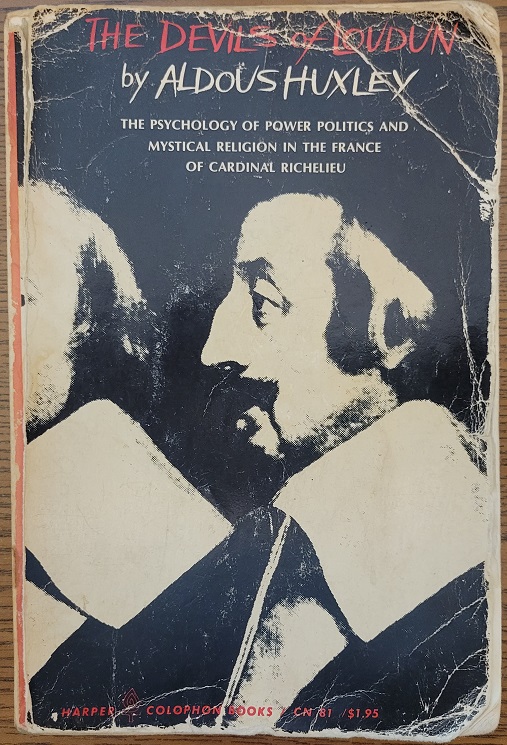

The other Huxley book I revisited recently was his only book-length history, The Devils of Loudon (1952). According to a sales slip still within the pages, I purchased my original copy on July 23, 1969 at a Bookmasters on 3 West 42nd Street for $1.95:

But it was in such bad shape that I bought a fresh one.

The Devils of Loudun involves a priest, Urbain Grandier, who for political and personal reasons, was accused of causing demonic possession of a convent of nuns in 17th century France. The nuns obliged by putting on crazy shows for all who wished to watch. The book was turned into a play The Devils by John Whiting in 1960, a opera by Krzysztof Penderecki in 1969 (later revised), and a fun lurid movie by Ken Russell in 1971.

The Wikipedia entry on this book classifies it a “non-fiction novel,” which was not a term in use when it was first published. But Huxley’s novelistic instincts are evident from the opening pages when he describes Loudun:

At the city gates a corpse or two hung, moldering, from the municipal gallows. Within the wall, there were the usual dirty streets, the customary gamut of smells, from wood smoke to excrement, from geese to incense, from baking bread to horses, swine, and unwashed humanity. (p. 4)

This is not ostensibly objectionable despite Huxley having never had a whiff of 17th century Loudun. But what he describes is not unreasonable. Nor do I mind so much descriptions like this during Grandier’s trial:

The Judges sat there, shifting in their chairs with unconcealed impatience, whispering among themselves, laughing, picking their noses, doodling with squeaky quills on the paper before them. Grandier looked at them, and suddenly it was manifest to him that there was no hope. (p. 199)

But there are more flagrant violations of the historian’s sacred trust. Part of the first chapter of Devils of Loudun is devoted to a marvelous account of the relationship that develops between Grandier and a young woman name Philippe Trincant, who Grandier is tutoring and (to use a modern word) grooming.

They sat in the same room, but not in the same universe. No longer a child, but not yet a woman, Philippe was the inhabitant of that rosy limbo of phantasy which lies between innocence and experience. Her home was not at Loudun, nor among these frumps and bores and boors, but with a god in a private Elysium, transfigured by the radiance of dawning love and imaginary sex. Those dark eyes of his, those mustaches, those white and well-kept hands — they haunted her like a guilty conscience. And what wit he had, what profundity of knowledge! An archangel, as wise as he was beautiful and as kind as he was wise. And he thought her clever, he praised her diligence; above all he had a certain way of looking at her. Was it possible that he . . . ? But no, no, it was sacrilegious even to think such thoughts, it was a sin. But how could she ever confess it — to him? (p. 31)

Then comes the day when she does confess that she loves him.

”At last,” Grandier said to himself, “at last!”

And now it was all plain sailing — just a matter of carefully graduated words and gestures, of a tenderness modulating by insensible degrees from the professionally Christian to the Petrarchian, and from the Petrarchian to the all too human and the self-transcendently animal. (p. 33)

Two pages later:

Then one day, in the middle of his story about King Francis’s drinking cups for debutantes — those flagons engraved on the inside with amorous postures, which revealed themselves a little more completely with every sip of the concealing wine — she interrupted him with the curt announcement that she was going to have a baby, and immediately burst into a paroxysm of uncontrollable sobbing. (p. 35)

It’s quite an enrapturing read, but is it history? There certainly existed a young woman named Philippe Trincant who did become pregnant and Grandier was widely suspected of being the father, but all the embroidered details are entirely fabricated. Huxley did a lot of research for this book, but he also imagined much else.

But it’s a tough call sometimes. I’ve read historical accounts of burnings at the stake that have restricted themselves to only the known facts and the testimony of eyewitnesses, and others (like Huxley’s) that attempt to convey what the experience must truly have been like. I hesitate to condemn the latter approach. Truth often exists beyond the realm of facts.

Because the 17th century is a very distant country, Huxley attempts to put much of this history into context. This was a particularly dangerous time to be accused of witchcraft, not only in France but other countries including America. (The Salem witch trials were in the 1690s.) Chapter 5 of The Devils of Loudun covers the historical rise and fall of witchcraft, but I began to harbor some doubts of its reliability when Huxley began discussing the gathering of witches known as a “sabbath” (pp. 136–7). This is something that modern historians no longer believe occurred.

At the time of writing Devils of Loudun, Huxley was particularly sympathetic to the history and practice of mysticism. (The Perennial Philosophy, his comparative study of mysticism, dates from 1945.) And while Devils of Loudun explores an interpretation of the possession in terms of “modern” (that is, mid-20th-century) psychology, interpretations involving mysticism also play a role that spills into an epilogue.

But it gets worse. In Chapter 7, Huxley asks “Do devils exist?”

And if so, were they present in the bodies of Sœur Jeanne and her fellow nuns? As with the notion of possession, I can see nothing intrinsically absurd or self-contradictory in the notion that there may be nonhuman spirits, good, bad and indifferent. Nothing compels us to believe that the only intelligences in the universe are those connected with the bodies of human beings and the lower animals.

The only excuse for the next cringeworthy sentence is that Huxley had been following some of the research done at Duke University (and elsewhere) into extra-sensory perception, but with a gullibility that is fatal to the historian.

If the evidence for clairvoyance, telepathy and prevision is accepted (and it is becoming increasingly difficult to reject it), then we must allow that there are mental processes which are largely independent of space, time, and matter. And if this is so, there seems to be no reason for denying a priori that there may be nonhuman intelligences, either completely incarnate, or else associated with cosmic energy in some way of which we are still ignorant. (p. 173)

Do you know what “cosmic energy” is? Neither do I.

For the reader still not exhausted by Huxley’s forays into mysticiam, the Epilogue is devoted to means of self-transcendence, and of course there are good ways and bad ways. The bad ways he terms “downward self-transcendence” of which he names three paths: “Drugs, elementary sexuality and herd-intoxication” (321).

Huxley’s attitude to drugs is exactly what you might expect from a book published in 1952:

For the drug-taker, the moment of spiritual awareness (if it comes at all) gives place very soon to subhuman stupor, frenzy or hallucination, followed by dismal hangovers and, in the long run, by a permanent and fatal impairment of bodily health and mental power. Very occasionally a single “anesthetic revelation” may act, like any other theophany, to incites its recipient to an effort of self-transformation and upward self-transcendence. But the fact that such a thing sometimes happens can never justify the employment of chemical methods of self-transcendence. (p. 324)

Just say no!

But here’s the punchline:

The Devils of Loudun was published in October 1952. (I’m using Sybille Bedford’s biography of Huxley for this chronology.) In May 1953, Huxley had his first experience with mescaline and judging from the subsequent The Doors of Perception (1954) he had apparently changed his mind on the subject.

But that’s another of Huxley’s intellectual evolutions.