Building a Virginal: The First Jack

April 24, 2023

New York, N.Y.

In a harpsichord, a finger presses a key down and the tail end of the key goes up. On the end of the key sits a wooden jack with a plastic plectrum that plucks the string.

Pressing a key on the virginal, watching the jack ascend and the plectrum pluck the string, and hearing the distinctive harpsichord twang — this is the event I’ve been anticipating even before I recieved the box containing the Zuckermann Troubadour Virginal kit.

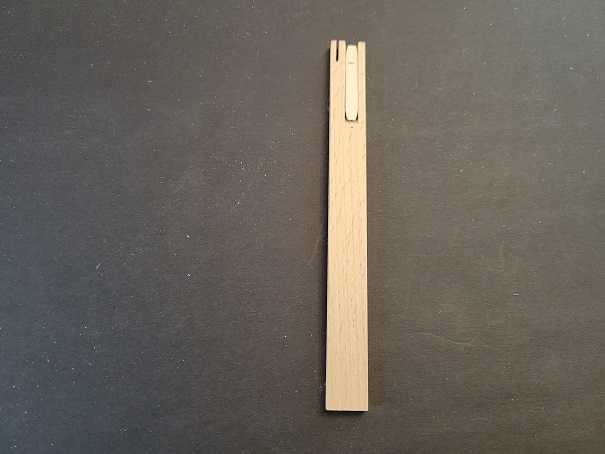

The jacks in that kit are packaged in a plastic-wrapped block, 8 wide and 7 deep:

That’s a total of 56, so I only have one to spare. The vertical slot at the top is for a piece of cloth that serves to damp the string when it’s not being plucked. The light part is known as a tongue.

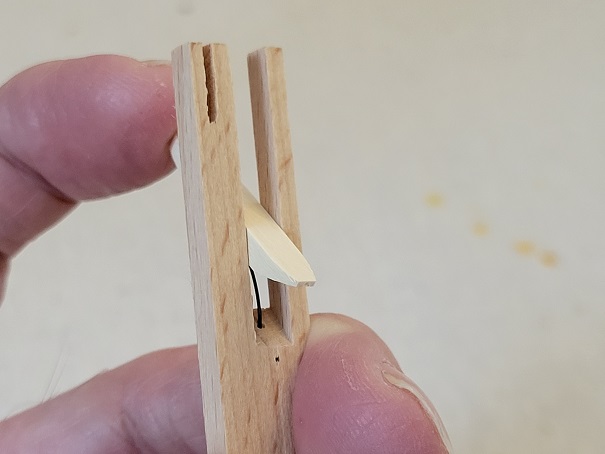

Here’s the front of a jack that faces towards the string.

Look closely, and you’ll see a little slit in the tongue. That’s for the plectrum to stick out. The back of the jack looks about the same except for a metal spring that allows the tongue to swing out of the way when the key is released:

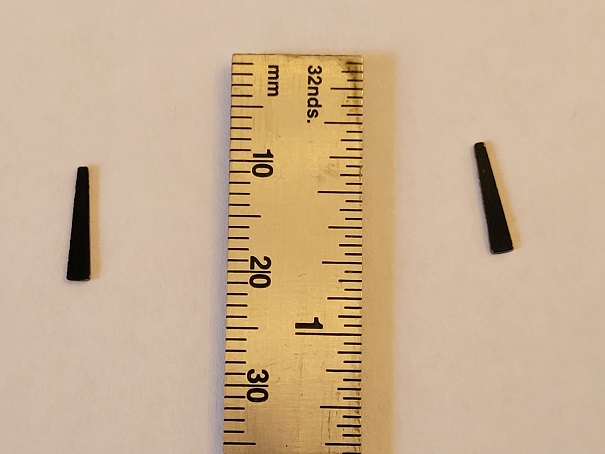

Back in the old days, the plectra were made from the shaft of bird feathers, and some people still do that, but these days they’re usually made of plastic. The plectra that Zuckermann supplies with the Troubadour Virginal kit are made of celcon, and are 0.02 inches in thickness:

The plectra are said to have a flat bottom and a rounded top, but I can’t tell the difference visually. My finger, however, can detect rougher and smoother sides. On the plectrum on the left, the rougher side (which I assume is the bottom) is up; on the right, the smoother side is up. There are also sources for purchasing harpsichord plectra of various sizes.

The plectrum is carefully inserted through the back of the jack using needle nose pliers. These pliers must have smooth jaws; otherwise, you risk crimping the plectrum. The plectrum must then be carefully carved to create a pleasant tone, an exercise known as “voicing.” Zuckermann has a video and another on this process, and it’s the part of the job that scares me the most.

The jacks that come with the kit are about 7/8” too long, and the bottoms must be sawed off. Initially, the plectrum should sit just below the string (according to the Construction Manual p. 49), but later on it is said that the plectrum should be 3/64” below the string and eventually (as the cloth on the ends of the keys becomes compressed), 1/16” below the string (p. 52). The jacks are also too light, and some lead must be inserted to weigh them down.

Too impatient was I to carve up my first plectrum, so as soon as I got everything ready, I just dropped it in and celebrated the event in this video:

That was April 20th (Construction Day 19), but that’s as far as I got.

I’m building the virginal in our little house in the Catskills, and the next day we drove into New York City for nine days, starting with three concerts at the 92nd Street Y featuring the ensemble Wild Up playing the music of Julius Eastman. We’ll also be seeing the Imani Winds tomorrow, the New York Philharmonic on Thursday, and a recital by tenor Allan Clayton (who we’ve seen in the past year at the Metropolitan Opera in the title roles of Brett Dean’s Hamlet and Benjamin Britten’s Peter Grimes) at the Park Avenue Armory.

Work on the virginal is scheduled to resume on April 30th, when I hope to prepare and install the 10 jacks for the notes B3, C4, D4, E4, G4, A4, C5, D5, E5, and F5, allowing me to play the first four measures of J.S. Bach’s Prelude in C Major.